DSM 5 Psychopath Criteria

Explore our free, printable template with DSM-5 criteria for disorders related to psychopathy, designed for quick reference and patient education.

What is psychopathy?

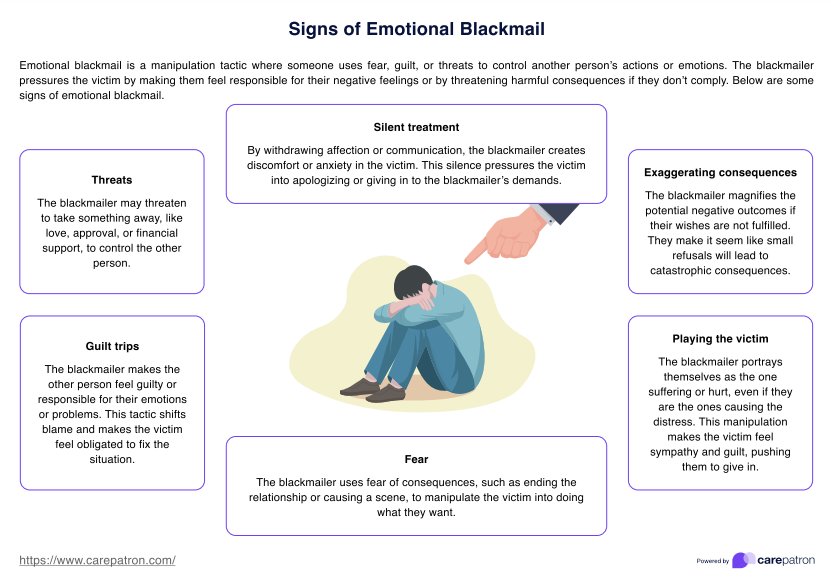

Psychopathy is a complex personality disorder characterized by a combination of interpersonal, affective, and antisocial behavioral syndromes. It is often associated with a lack of empathy, manipulative behavior, and a tendency towards antisocial behaviors, such as criminal behavior.

Psychopathy is considered a severe form of antisocial personality disorder, even sharing some features with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. The psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R) developed by Dr. Robert Hare (1991) lists these traits and symptoms:

- Factor 1 (Interpersonal/affective): Includes traits such as superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, manipulative behavior, lack of remorse or guilt, shallow affect, and callous lack of empathy.

- Factor 2 (Social deviance): Encompasses traits like the need for stimulation, proneness to boredom, parasitic lifestyle, poor behavioral controls, impulsivity, irresponsibility, and a history of juvenile delinquency.

This perspective is based on the observation that individuals with psychopathy exhibit more extreme antisocial and interpersonal behaviors compared to those with a diagnosis of ASPD alone. However, it's important to note that not all individuals with ASPD meet the criteria for psychopathy, as defined by tools like the PCL-R.

Causes of psychopathy

The exact causes of psychopathy are not fully understood, but it is believed to result from a complex interplay of neurobiological, genetic, and environmental factors (Tiihonen et al., 2019). Research suggests that abnormalities in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex may contribute to the emotional and behavioral characteristics of psychopathy (Junewicz & Billick, 2021). Environmental factors such as early childhood trauma, neglect, and exposure to violence may also play a role in developing psychopathic traits.

DSM 5 Psychopath Criteria Template

DSM 5 Psychopath Criteria Example

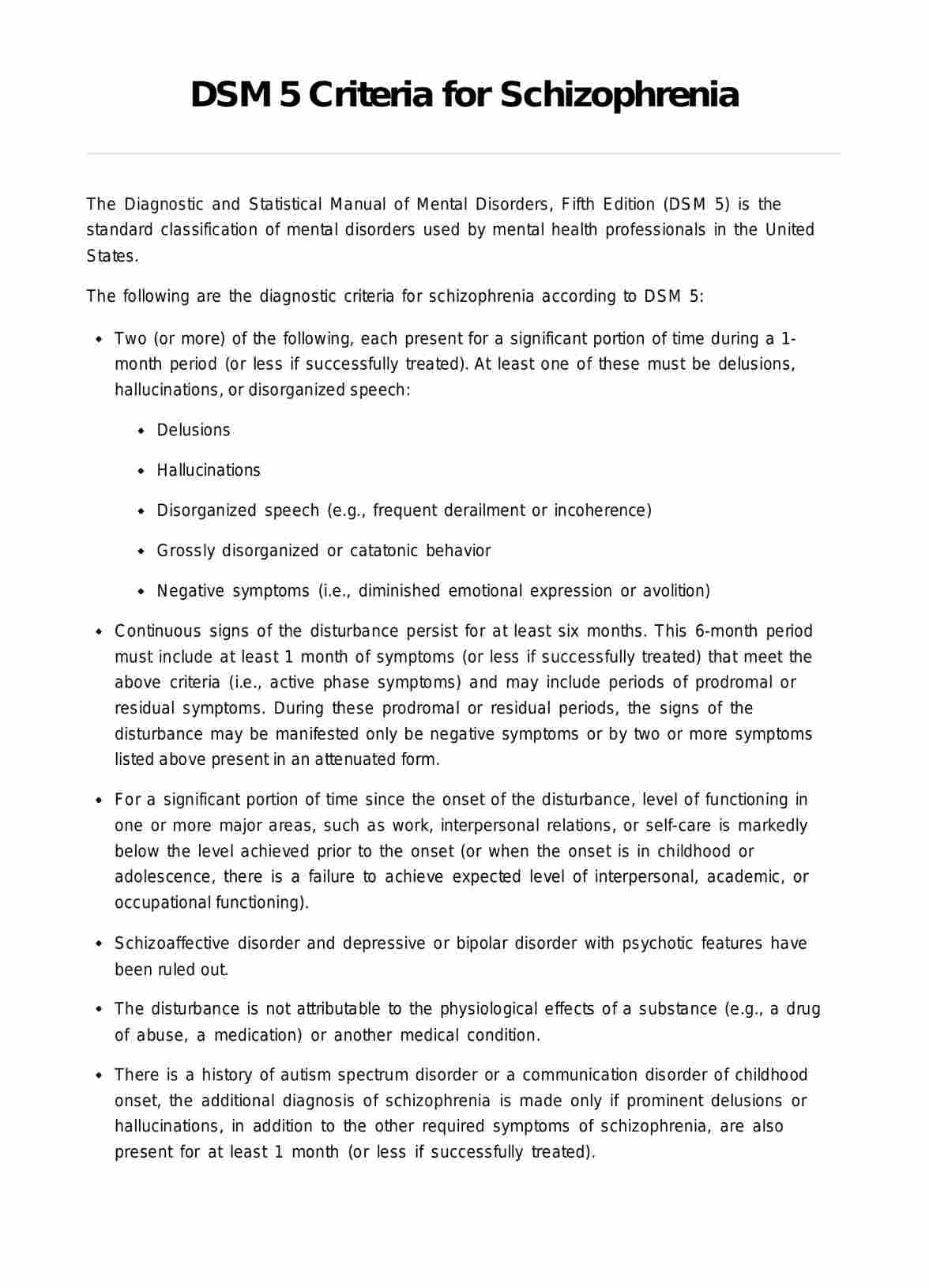

Is psychopathy in the DSM 5?

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) replaced psychopathy with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Presently, the fifth edition (DSM-5), is the standard classification of mental and personality disorders used by mental health professionals in the United States, used for diagnosis, treatment planning, and research. The DSM-5 provides a common language and standard criteria for the classification of mental disorders.

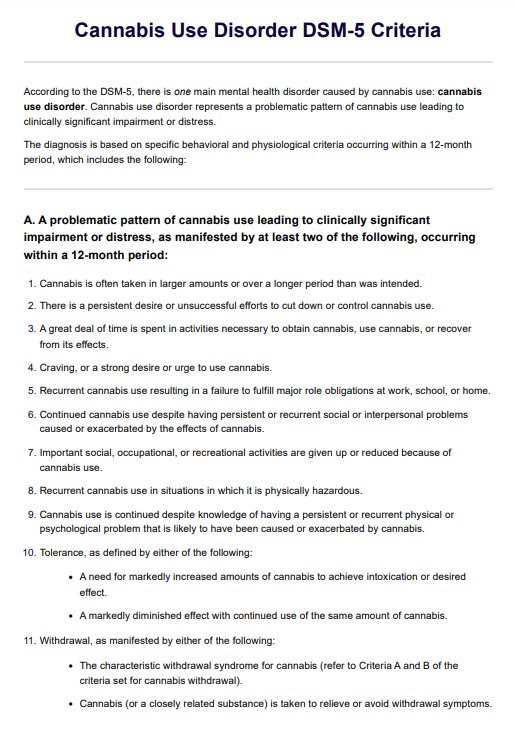

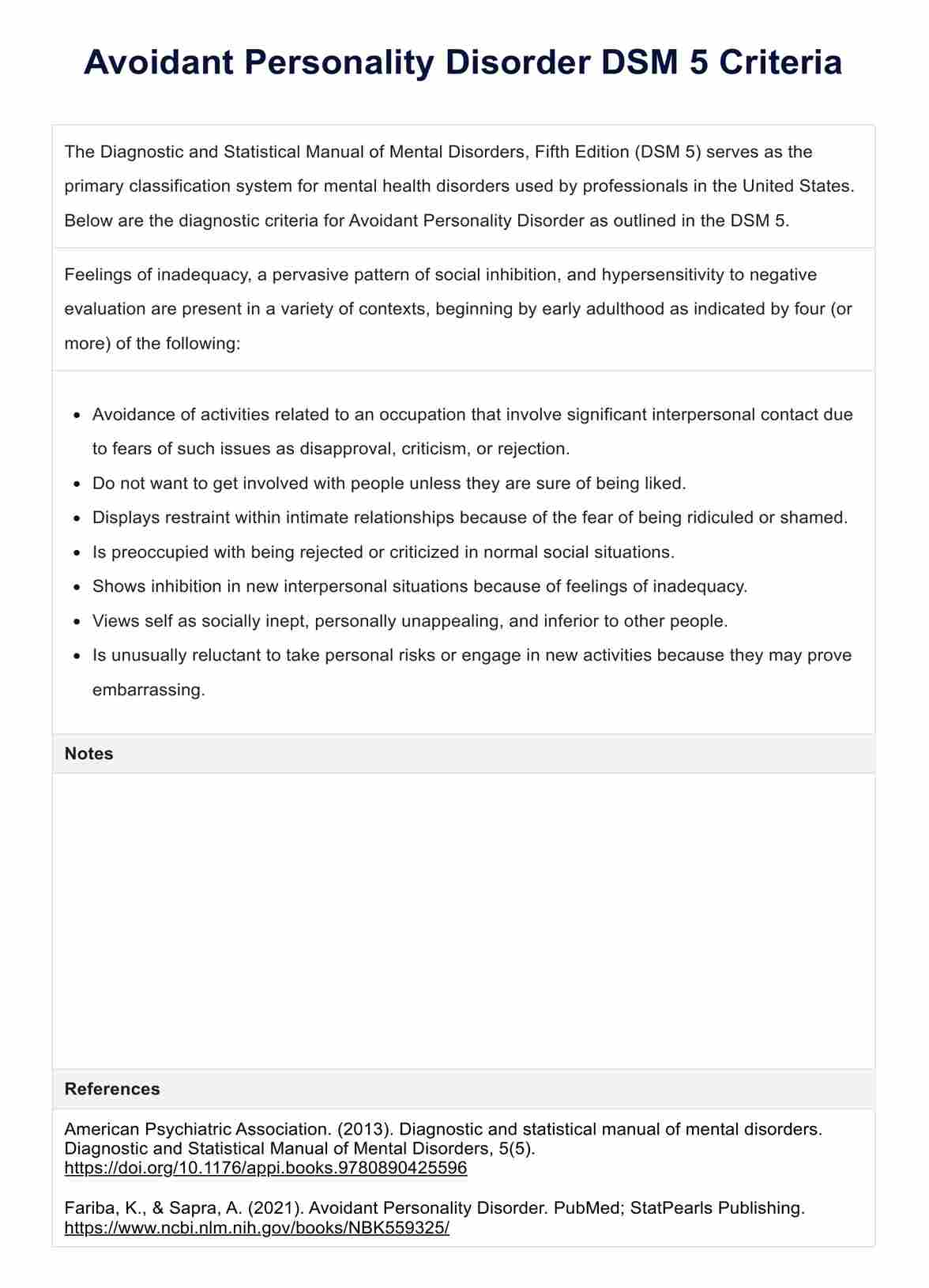

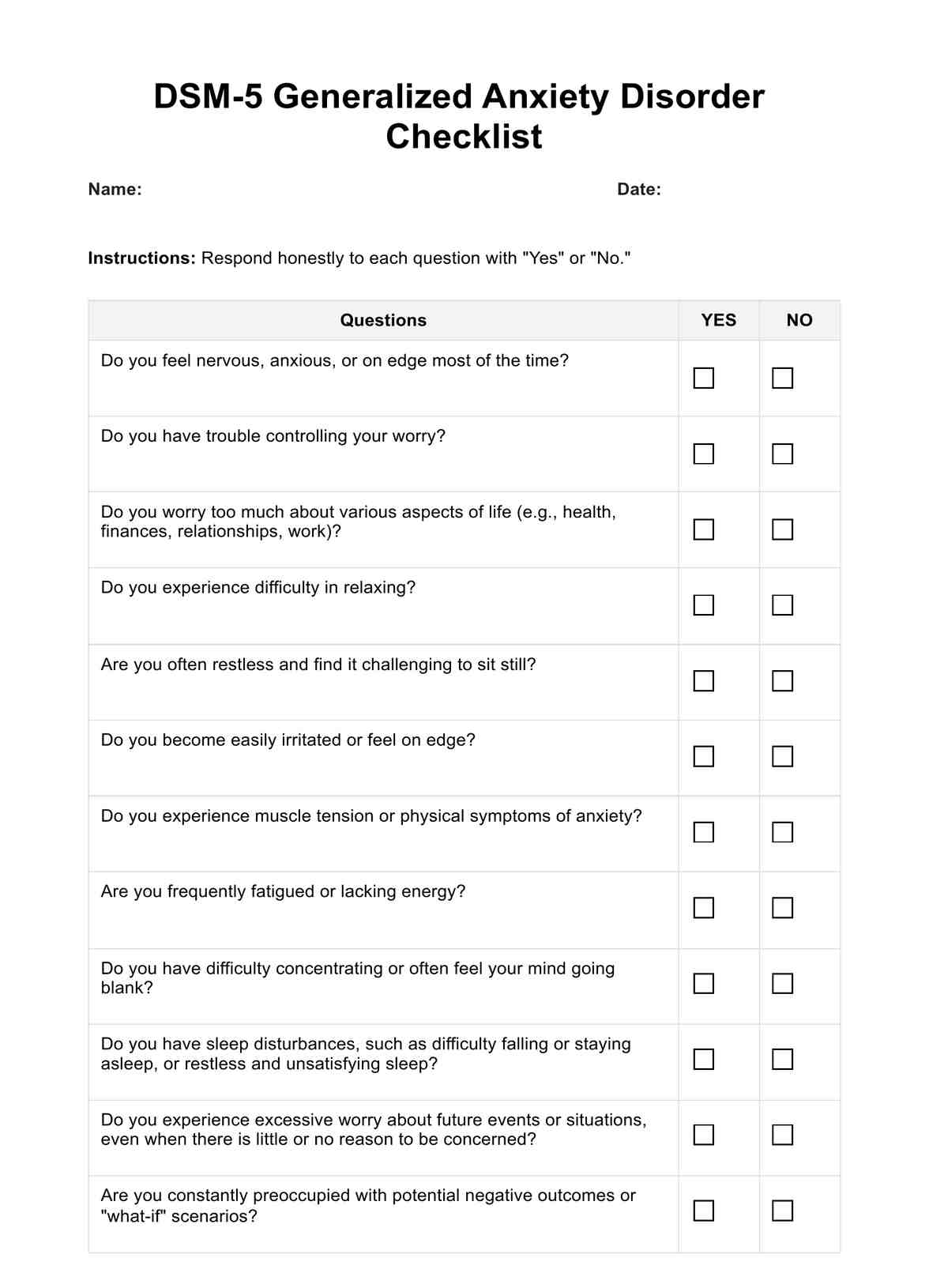

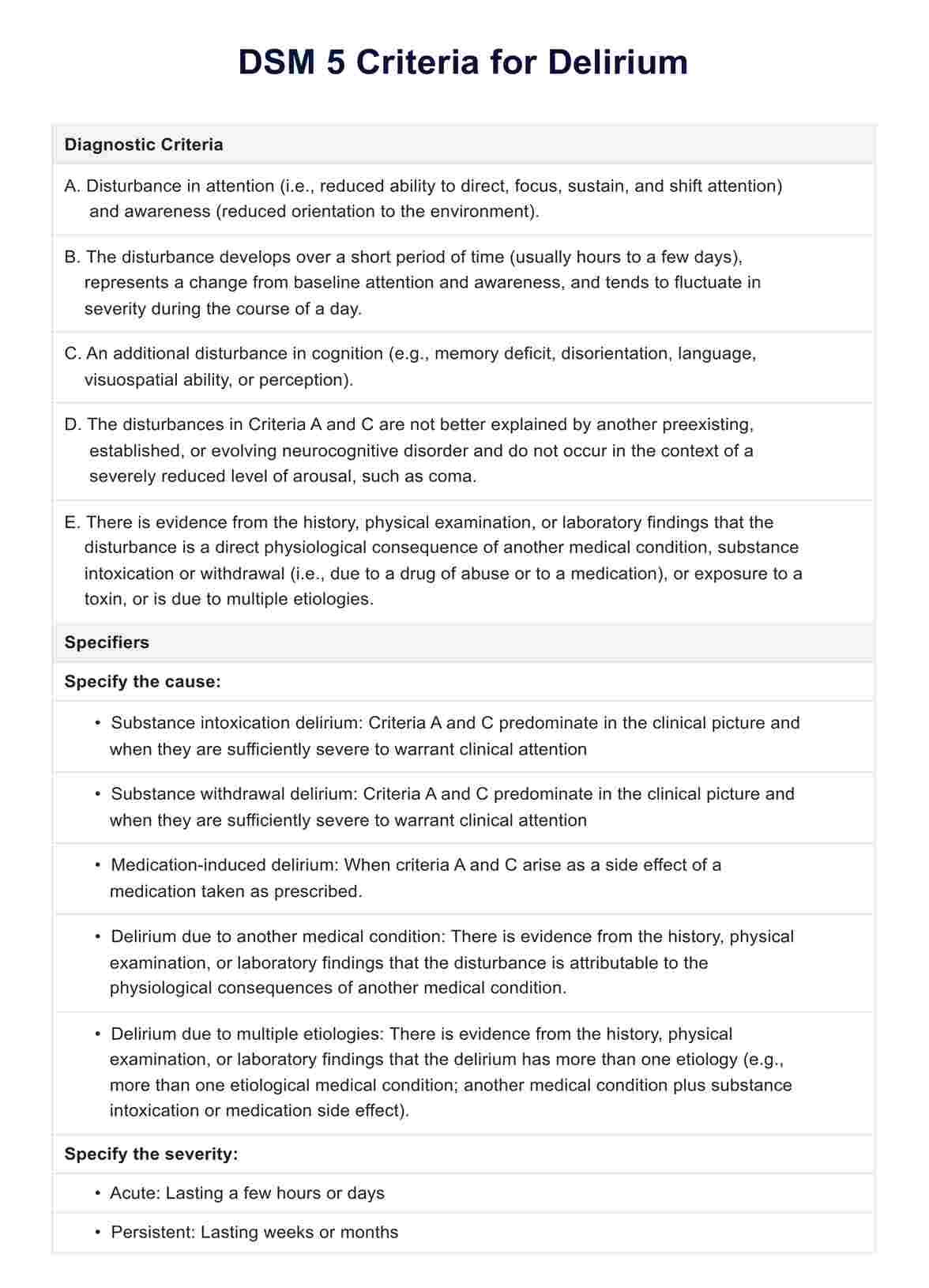

DSM 5 disorders closest to psychopathy

The closest related disorders are conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). These disorders share some overlapping traits with psychopathy, such as a disregard for social norms and the rights of others, as well as a lack of empathy. These disorders are often quoted in the discourse surrounding psychopathy.

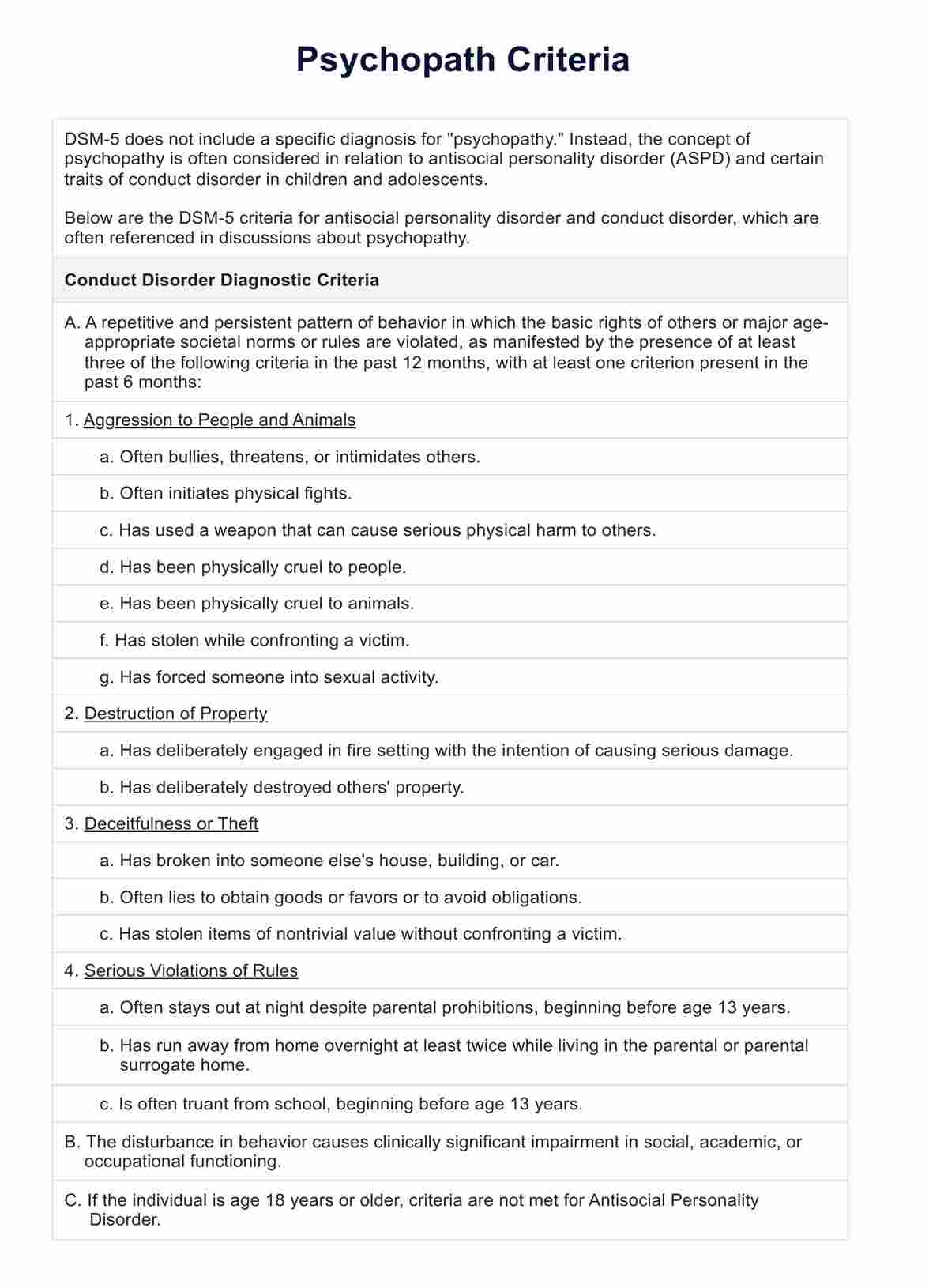

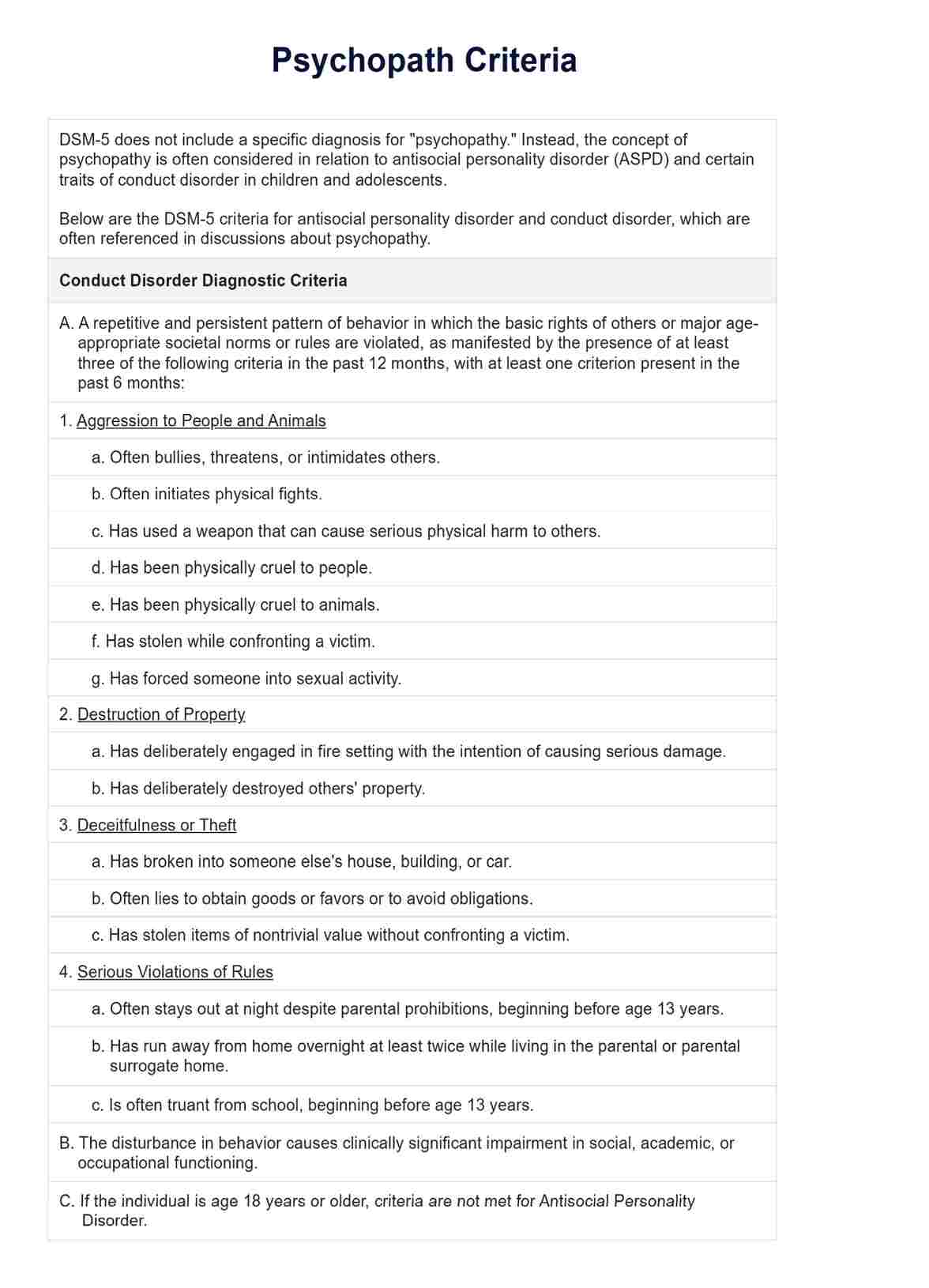

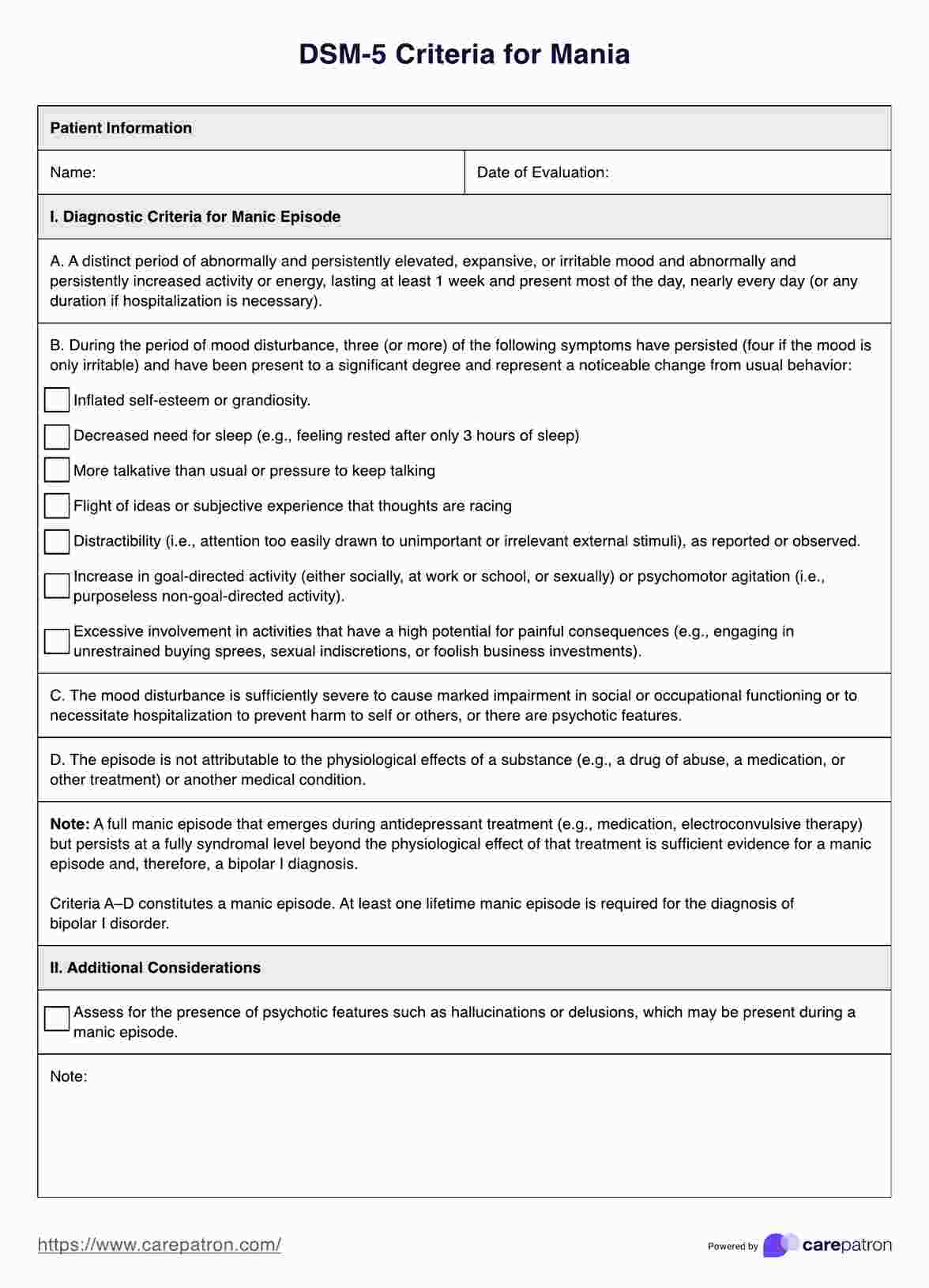

DSM 5 criteria for conduct disorder

Conduct Disorder is characterized by a repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated. The DSM-5 criteria for Conduct Disorder are below, including its specifiers:

Criterion A

A repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated, as manifested by the presence of at least three of the following criteria in the past 12 months, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 months:

- Aggression to people and animals

- Often bullies, threatens, or intimidates others.

- Often initiates physical fights.

- Has used a weapon that can cause serious physical harm to others.

- Has been physically cruel to people.

- Has been physically cruel to animals.

- Has stolen while confronting a victim.

- Has forced someone into sexual activity.

- Destruction of property

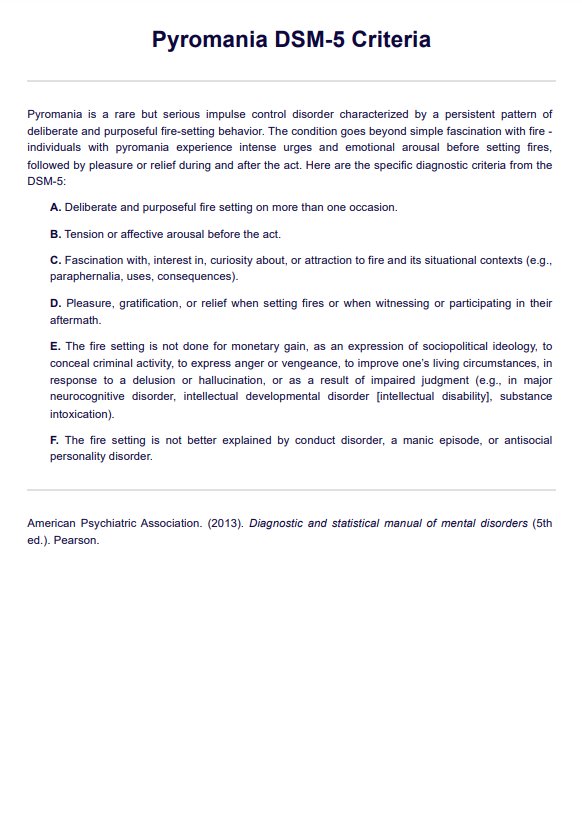

- Has deliberately engaged in fire setting with the intention of causing serious damage.

- Has deliberately destroyed others' property.

- Deceitfulness or theft

- Has broken into someone else's house, building, or car.

- Often lies to obtain goods or favors or to avoid obligations.

- Has stolen items of nontrivial value without confronting a victim.

- Serious violations of rules

- Often stays out at night despite parental prohibitions, beginning before age 13 years.

- Has run away from home overnight at least twice while living in the parental or parental surrogate home.

- Is often truant from school, beginning before age 13 years.

Criterion B

The disturbance in behavior causes clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning.

Criterion C

If the individual is age 18 years or older, criteria are not met for Antisocial Personality Disorder.

Specifiers for conduct disorder

A mental health professional must specify the type based on when the symptoms arose:

- Childhood-onset type: Individuals show at least 1 symptom characteristic of conduct disorder prior to age 10 years.

- Adolescent-onset type: Individuals show no symptom characteristic of conduct disorder prior to age 10 years.

- Unspecified onset: Criteria for a diagnosis of conduct disorder are met, but there is not enough information available to determine whether the onset of the first symptom was before or after age 10 years.

In addition, severity must also be specified:

- Mild: Few if any conduct problems in excess of those required to make the diagnosis are present, and conduct problems cause only minor harm to others.

- Moderate: The number of conduct problems and the effect on others are intermediate between "mild" and "severe."

- Severe: Many conduct problems in excess of those required to make the diagnosis are present, or conduct problems cause considerable harm to others.

Lastly, the mental health professional must specify whether the patient presents with limited prosocial emotions. This type is closest to psychopathy.

To qualify for this specifier, an individual must have displayed at least 2 of the following characteristics persistently over at least 12 months and in multiple relationships and settings. These characteristics reflect the individual’s typical pattern of interpersonal and emotional functioning over this period and not just occasional occurrences in some situations.

- Lack of remorse or guilt: Does not feel bad or guilty when he or she does some thing wrong (exclude remorse when expressed only when caught and/or facing punishment). The individual shows a general lack of concern about the negative consequences of his or her actions. For example, the individual is not remorseful after hurting someone or does not care about the consequences of breaking rules.

- Callous—lack of empathy: Disregards and is unconcerned about the feelings of others. The individual is described as cold and uncaring. The person appears more concerned about the effects of his or her actions on himself or herself, rather than their effects on others, even when they result in substantial harm to others.

- Unconcerned about performance: Does not show concern about poor/problematic performance at school, at work, or in other important activities. The individual does not put forth the effort necessary to perform well, even when expectations are clear, and typically blames others for his or her poor performance.

- Shallow or deficient affect: Does not express feelings or show emotions to others, except in ways that seem shallow, insincere, or superficial (e.g. - actions contradict the emotion displayed; can turn emotions “on” or “off’ quickly) or when emotional expressions are used for gain (e.g. emotions to manipulate or intimidate others).

Multiple information sources are necessary to assess the criteria for the specifier. In addition to the individual’s self-report, it is necessary to consider reports by others who have known the individual for extended periods of time (e.g., parents, teachers, co-workers, extended family members, peers).

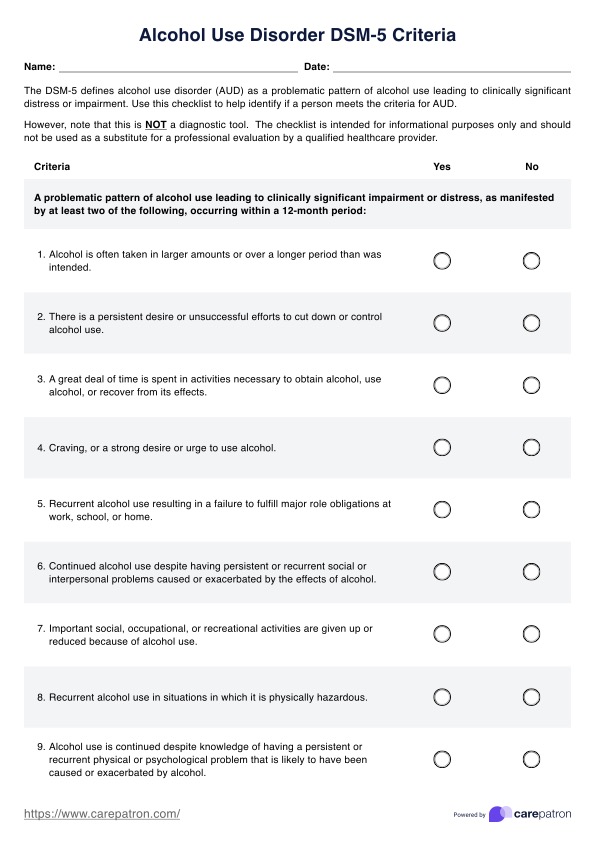

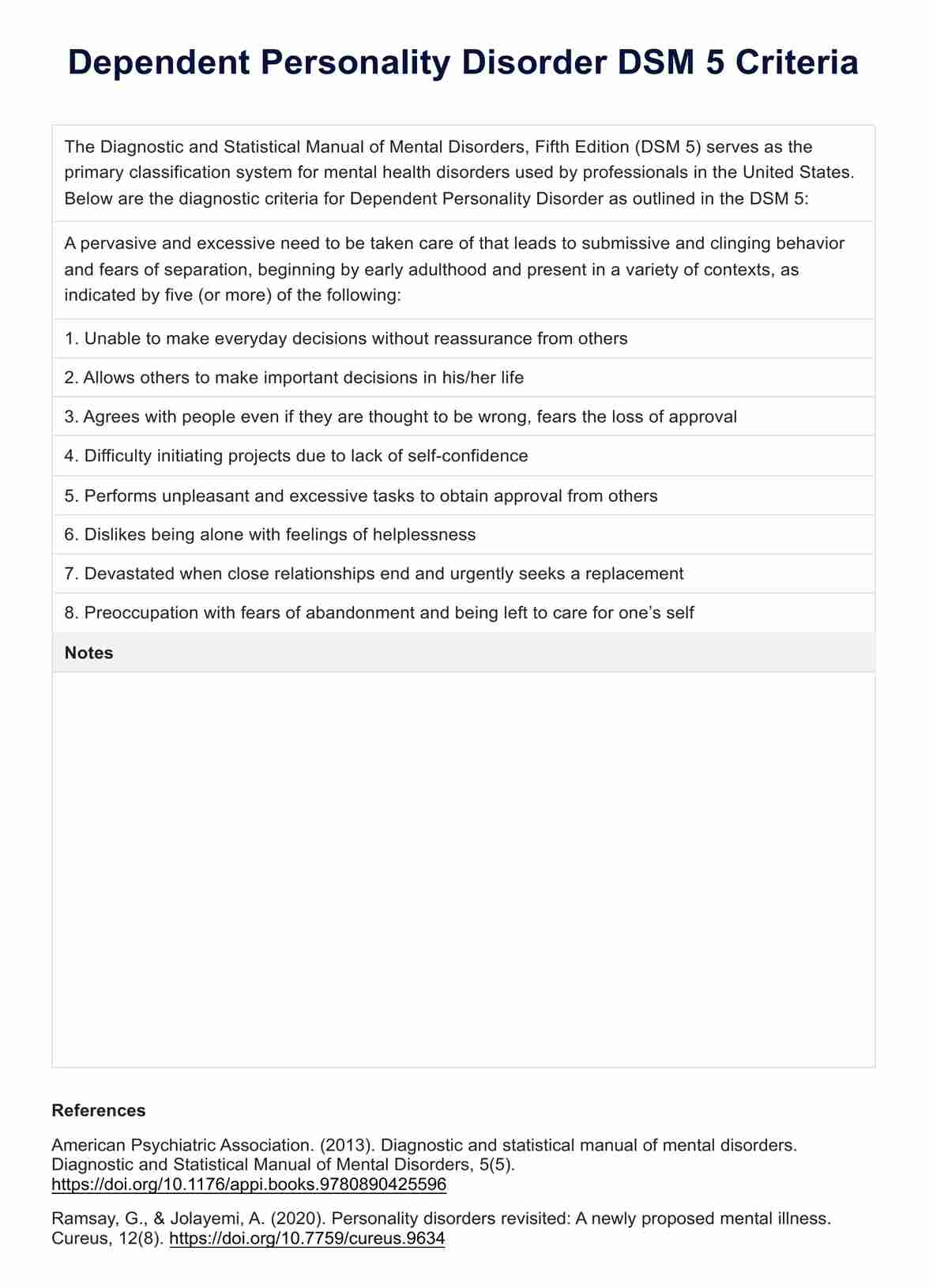

DSM 5 criteria for antisocial personality disorder

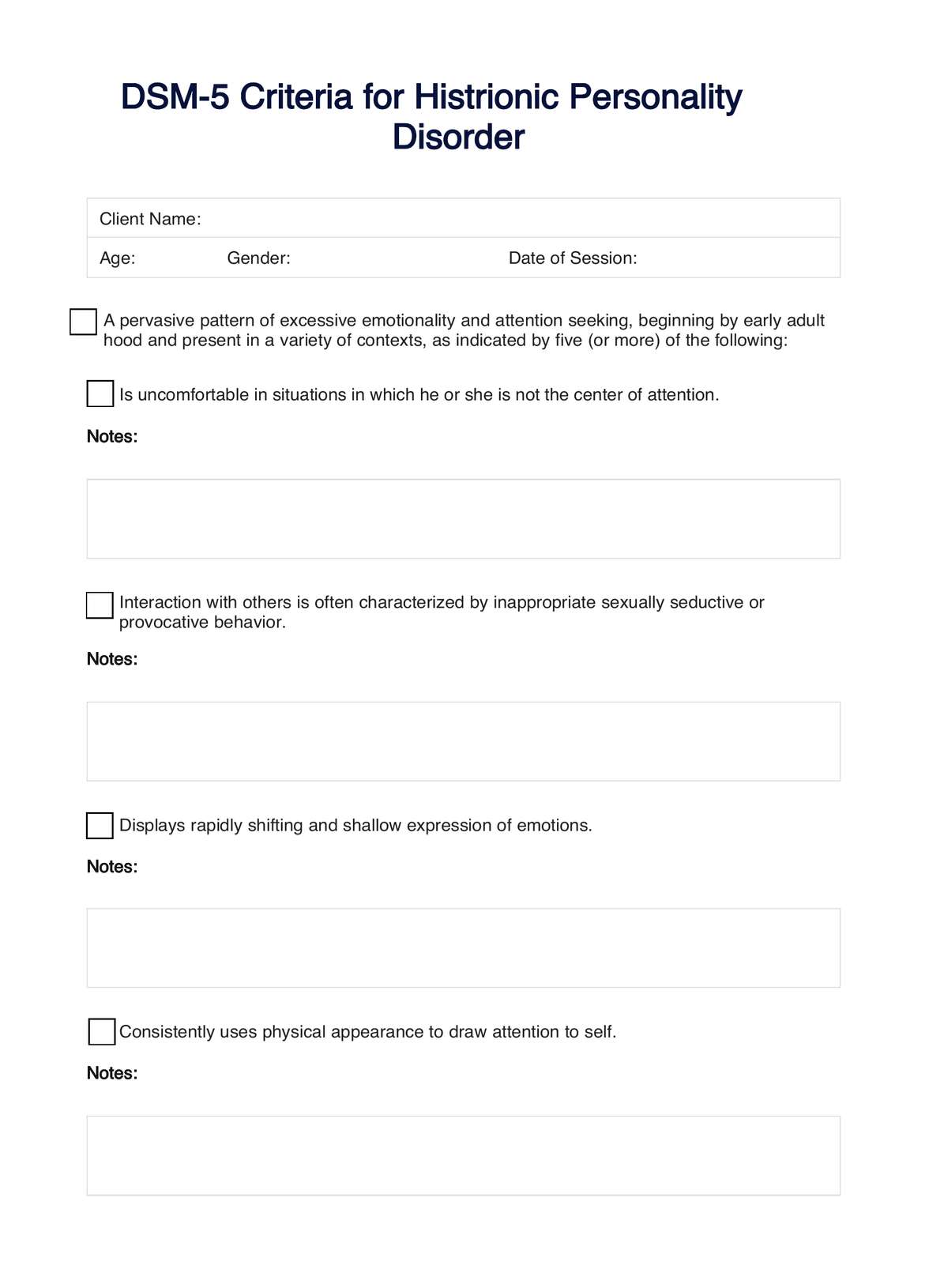

Antisocial Personality Disorder is defined by a pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others, a trait it shares with histrionic personality disorder in terms of attention-seeking behaviors. The DSM-5 criteria for ASPD include:

Criterion A

A pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others, occurring since age 15 years, as indicated by 3 (or more) of the following:

- Failure to conform to social norms with respect to lawful behaviors

- Deceitfulness

- Impulsivity or failure to plan ahead

- Irritability and aggressiveness

- Reckless disregard for the safety of self or others

- Consistent irresponsibility

- Lack of remorse

Criterion B

The individual is at least age 18 years.

Criterion C

There is evidence of conduct disorder with onset before age 15 years.

Criterion D

The occurrence of antisocial behavior is not exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

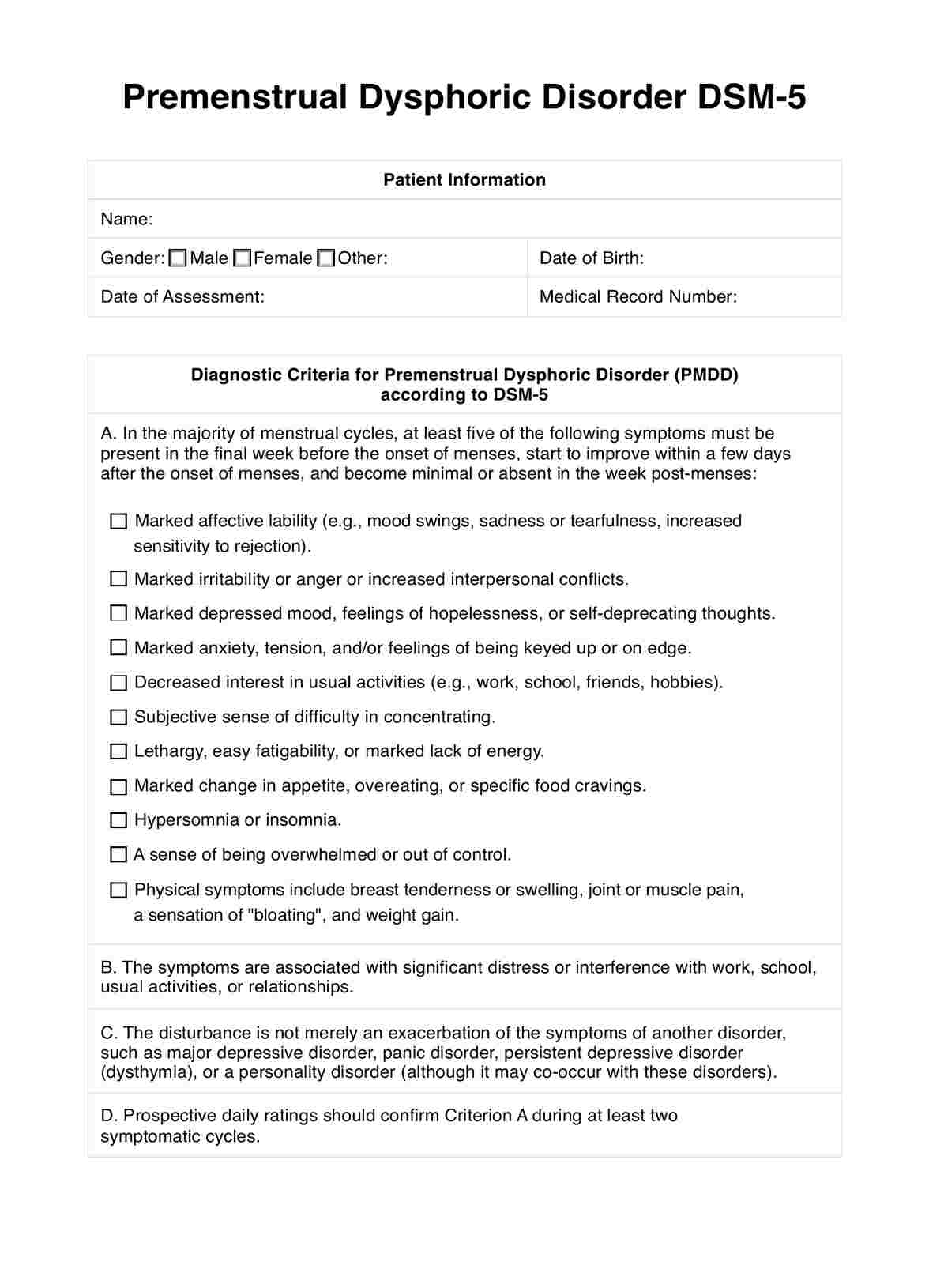

How do healthcare professionals diagnose psychopathy?

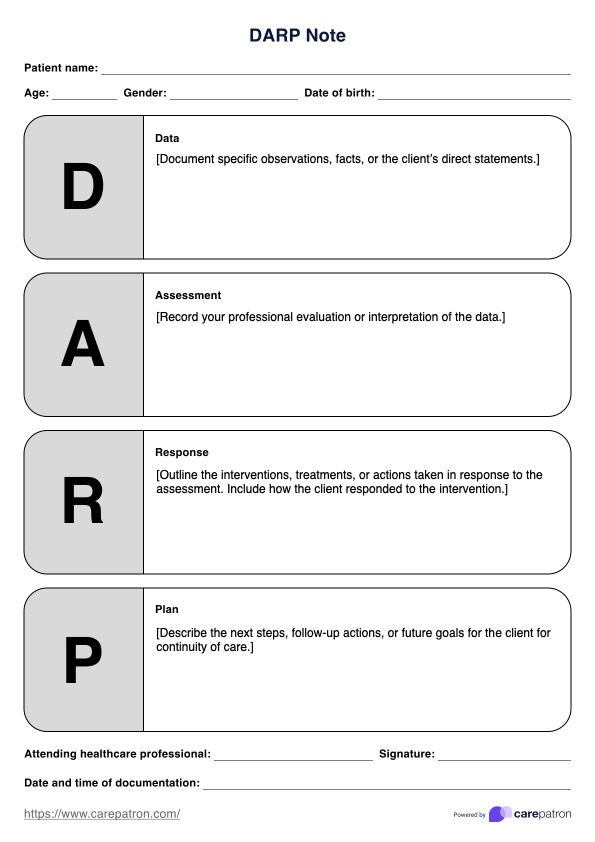

Diagnosing psychopathy involves a comprehensive assessment that goes beyond the criteria for related disorders like Conduct Disorder and Antisocial Personality Disorder. Mental health professionals use a combination of clinical interviews, behavioral observations, and standardized assessment tools to evaluate the presence and severity of psychopathic traits. One of the most widely used tools for this purpose is the psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R).

Here are the assessments for diagnosing psychopathy:

- Clinical interviews: Detailed interviews with the individual, and sometimes with their family or others who know them well, to gather information about their behavior, relationships, and emotional functioning.

- Behavioral observations: Observations of the individual's behavior in different settings to assess their social interactions, emotional responses, and adherence to norms.

- Psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R): A 20-item assessment tool that evaluates specific traits and behaviors associated with psychopathy, such as glibness/superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, and lack of empathy. Each item is scored on a 3-point scale (0, 1, 2), with a maximum score of 40. Scores above a certain threshold (typically 30 in the United States) are indicative of psychopathy.

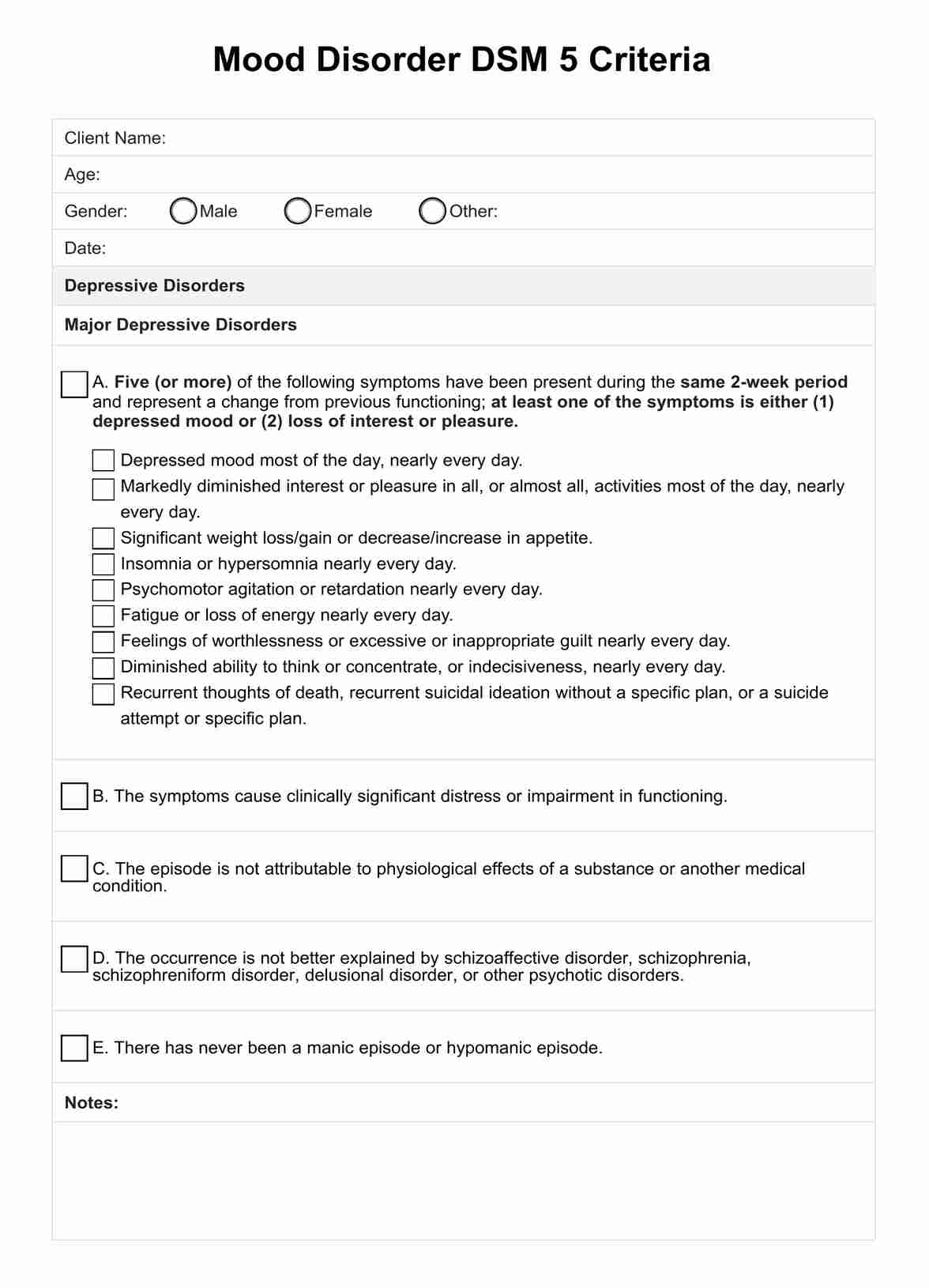

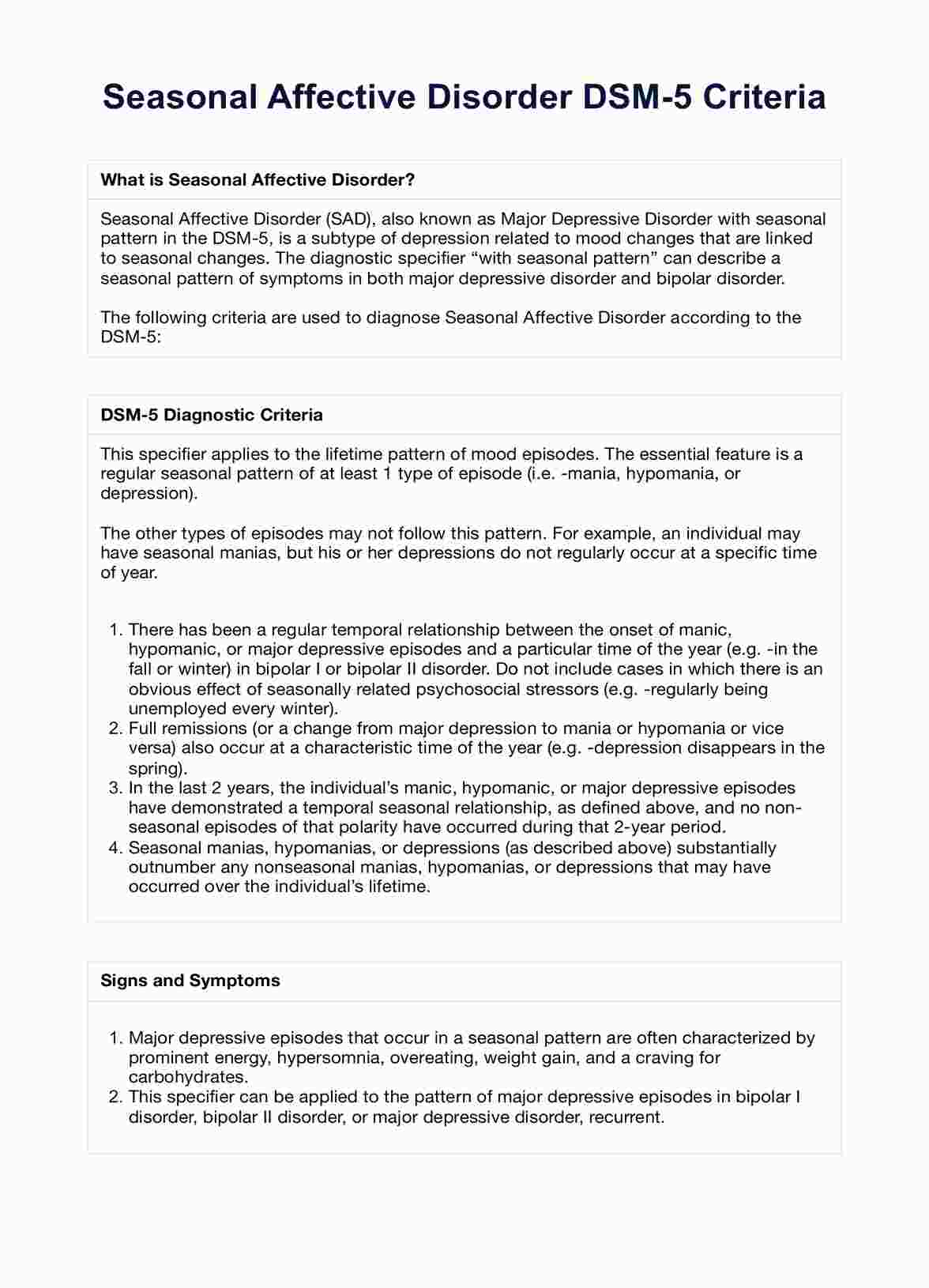

- Other psychological assessments: Additional tests and questionnaires may be used to assess related aspects of mental health, such as personality disorders, mood disorders, and risk for violent behavior.

It's important to note that diagnosing psychopathy is complex and should only be done by qualified mental health professionals. The assessment process is thorough and takes into account a wide range of factors to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

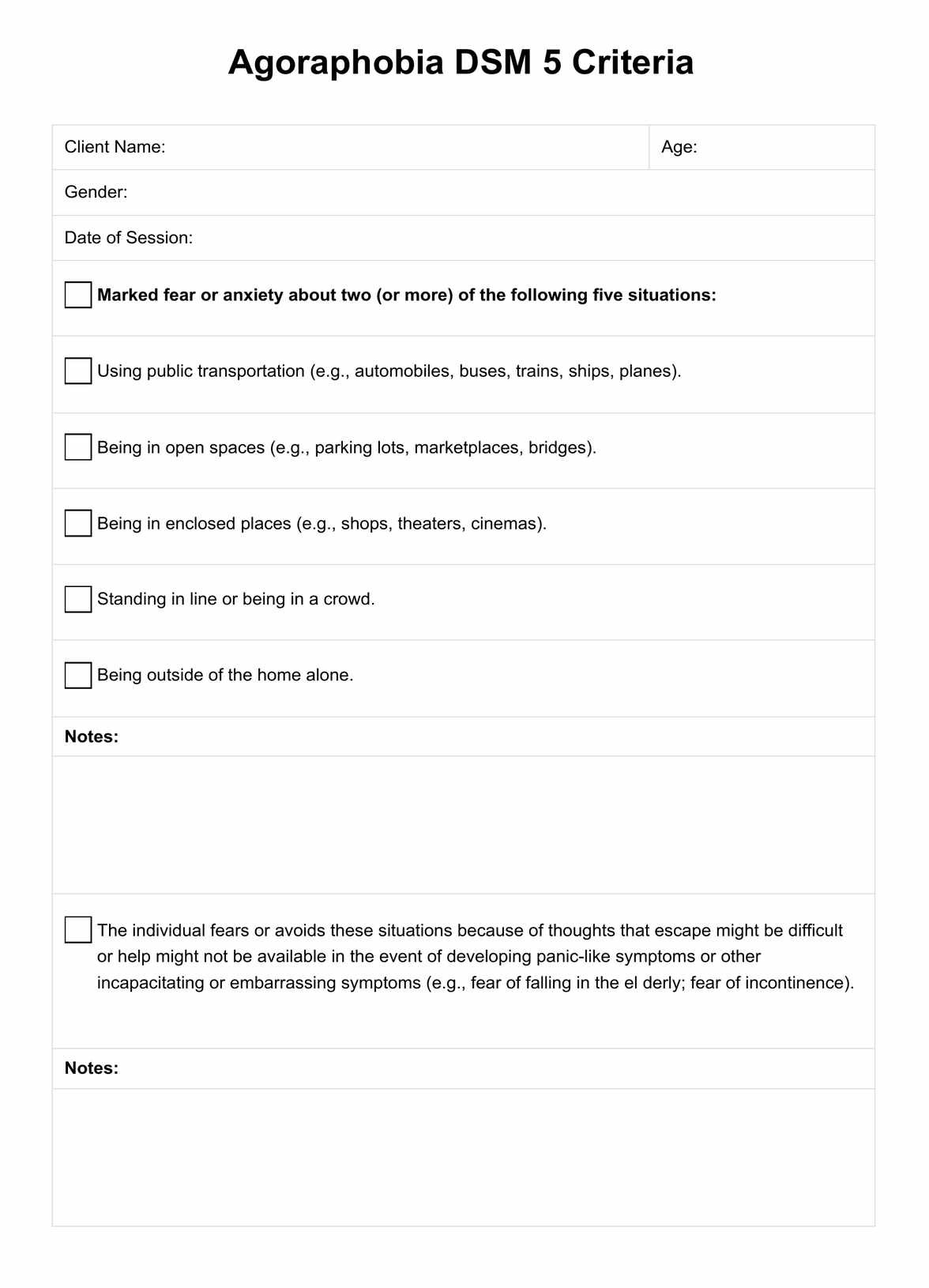

How is psychopathy treated and managed?

Treating and managing psychopathy is challenging due to the inherent nature of the condition, including a lack of remorse, empathy, and a tendency to manipulate others. However, some approaches have been explored to manage the behaviors associated with psychopathy.

Treatment approaches

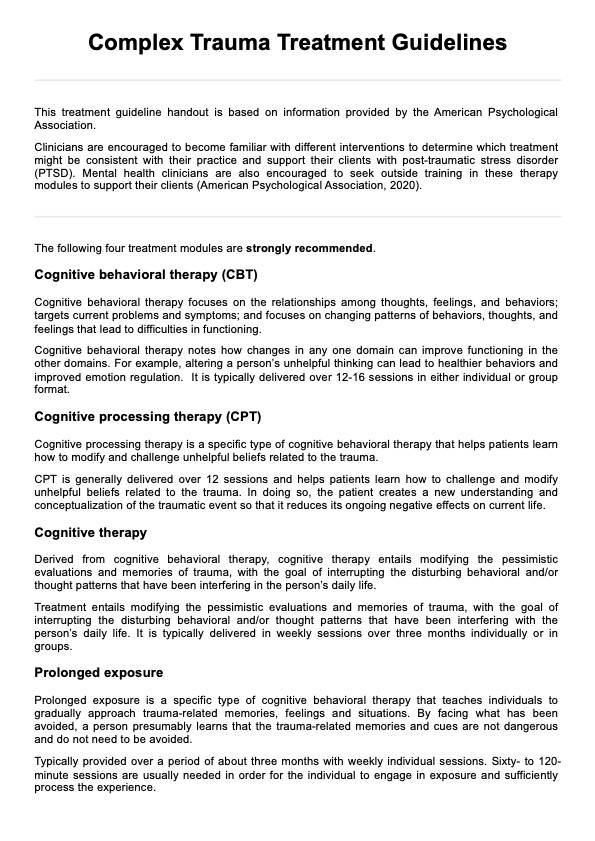

Effective treatment for psychopathy focuses on behavioral interventions and skills development. The following approaches have been utilized:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): While traditional CBT may have limited effectiveness, modified versions focusing on behavioral change, rather than changing underlying personality traits, can help manage some aspects of psychopathy.

- Therapeutic communities: Structured environments, such as those found in prisons or specialized treatment centers, can provide a controlled setting where individuals with psychopathic traits can learn pro-social behaviors.

- Skills training: Teaching specific skills, such as anger management or social skills, can help individuals with psychopathic traits navigate social situations more appropriately.

Management strategies

Managing psychopathy involves continuous monitoring and risk assessment to prevent harmful behaviors. The following strategies are commonly employed:

- Risk assessment: Regularly assessing the risk of violent or criminal behavior can help in developing appropriate management plans.

- Supervision and monitoring: Close supervision and monitoring in institutional settings or as part of community-based programs can help manage behavior.

- Legal and ethical considerations: Due to the potential for manipulation and deceit, it's important for professionals working with individuals with psychopathy to maintain clear boundaries and adhere to ethical standards.

It's important to note that there is no "cure" for psychopathy, and treatment primarily focuses on managing behaviors and reducing the risk of harm to others. Collaboration among mental health professionals, legal systems, and correctional institutions is often necessary for effective management.

Research on psychopathy

Recent research has delved into the complex world of psychopathy, uncovering intriguing insights into its brain basis and behavioral manifestations. Studies are beginning to shed light on the neurological underpinnings of psychopathic traits and their relationship with different forms of aggression.

A groundbreaking study by Nummenmaa et al. (2021) revealed significant alterations in brain areas related to emotions and their regulation in psychopathic criminal offenders and individuals with psychopathy-related traits in the general population. The research highlighted changes in brain structure and function that contribute to the emotional and behavioral characteristics of psychopathy.

Specifically, the study found lower gray matter density in the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior insula in psychopathic offenders, with similar associations between primary psychopathy traits and compromised cortical integrity in the same areas in a community sample. This suggests that similar neural alterations underlie criminal psychopathy and variation in everyday antisocial behavior in psychologically well-functioning individuals.

Verona et al. (2022) explored the relationship between different aspects of psychopathy and specific forms of aggression, emphasizing the role of power in psychopathy-related aggression. The study found that the impulsive facet of psychopathy was generally related to multiple forms of aggression, while the unique variance in the affective facet was primarily related to physical aggression.

Interestingly, the interpersonal facet of psychopathy showed a primary relationship with indirect aggression, such as relational and passive aggression. Additionally, the desire for power was found to be an independent explanatory construct for multiple forms of aggression proneness, highlighting the complex interplay between psychopathy, power, and aggression.

These studies provide valuable insights into the neural basis of psychopathy and the nuanced relationships between different psychopathy facets and forms of aggression. Understanding the brain alterations associated with psychopathy and the role of power in psychopathy-related aggression can inform the development of more effective interventions and management strategies for individuals with psychopathic traits.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), 5(5). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Blonigen, D. M., Hicks, B. M., Krueger, R. F., Patrick, C. J., & Iacono, W. G. (2005). Psychopathic personality traits: heritability and genetic overlap with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Psychological Medicine, 35(5), 637–648. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704004180

Hare, R. D. (1991). Psychopathy checklist—revised [database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01167-000

Hare, R. D. (2016). Psychopathy, the PCL-R, and criminal justice: Some new findings and current issues. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 57(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000041

Junewicz, A., & Billick, S. B. (2021). Preempting the Development of Antisocial Behavior and Psychopathic Traits. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 51(1). https://doi.org/10.29158/JAAPL.200060-20

Nummenmaa, L., Lukkarinen, L., Sun, L., Putkinen, V., Seppälä, K., Karjalainen, T., Karlsson, H. K., Hudson, M., Venetjoki, N., Salomaa, M., Rautio, P., Hirvonen, J., Lauerma, H., & Tiihonen, J. (2021). Brain basis of psychopathy in criminal offenders and general population. Cerebral Cortex, 31(9), 4104–4114. Oxford Academic. https://academic.oup.com/cercor/article/31/9/4104/6218172

Pisano, S., Muratori, P., Gorga, C., Levantini, V., Iuliano, R., Catone, G., Coppola, G., Milone, A., & Masi, G. (2017). Conduct disorders and psychopathy in children and adolescents: Aetiology, clinical presentation and treatment strategies of callous-unemotional traits. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 43(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-017-0404-6

Tiihonen, J., Koskuvi, M., Lähteenvuo, M., Virtanen, P. L. J., Ojansuu, I., Vaurio, O., Gao, Y., Hyötyläinen, I., Puttonen, K. A., Repo-Tiihonen, E., Paunio, T., Rautiainen, M.-R., Tyni, S., Koistinaho, J., & Lehtonen, Š. (2019). Neurobiological roots of psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry, 25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0488-z

Verona, E., McKinley, S. J., Hoffmann, A., Murphy, B. A., & Watts, A. L. (2022). Psychopathy facets, perceived power, and forms of aggression. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 14(3), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000562

Widiger, T. A., & Crego, C. (2018). Psychopathy and DSM‑5 psychopathology. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of Psychopathy (pp. 281–296). The Guilford Press.

Commonly asked questions

The DSM-5 does not have a specific diagnosis for psychopathy but includes criteria for related disorders such as conducted disorder and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), which share some traits with psychopathy.

Yes, psychopathy as a distinct diagnosis was removed from the DSM in its third edition and replaced with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).

The DSM does not distinguish between sociopaths and psychopaths. People believed to fall under these terms display symptoms of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).

-template.jpg)