Prone Knee Bend Test

Learn about the Prone Knee Bend Test and how it assesses radicular pain.

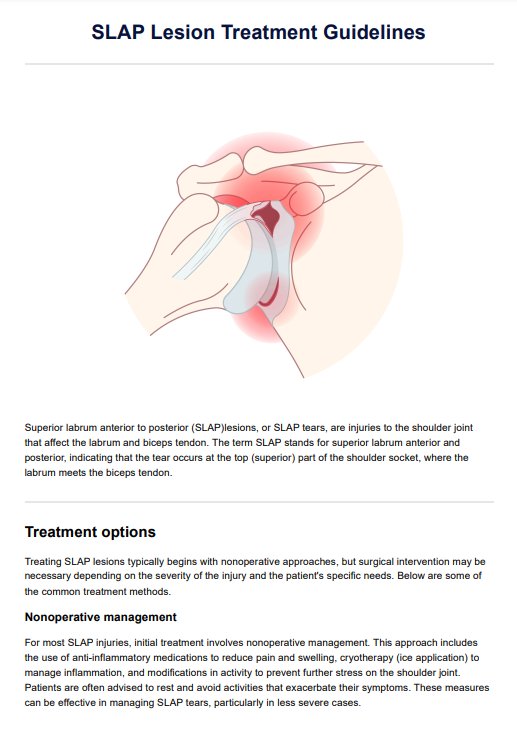

Understanding radicular pain

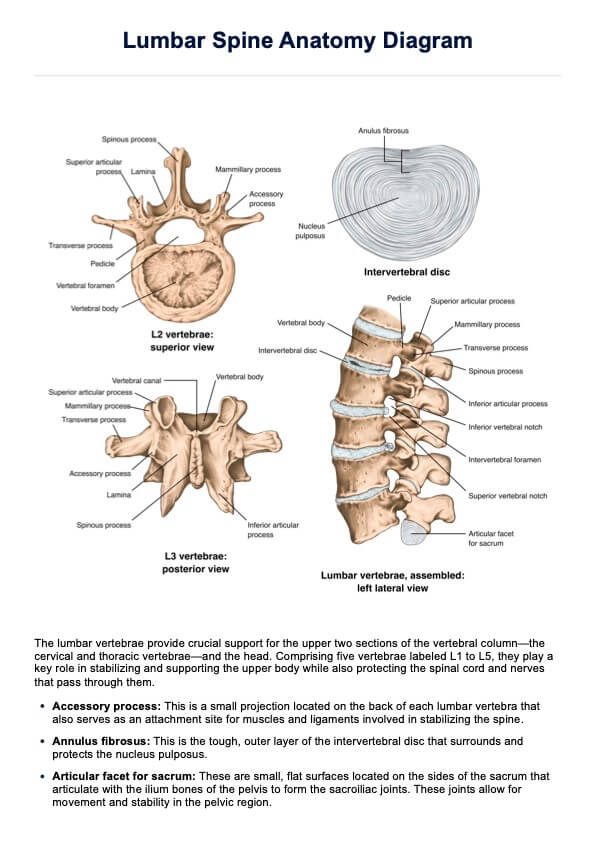

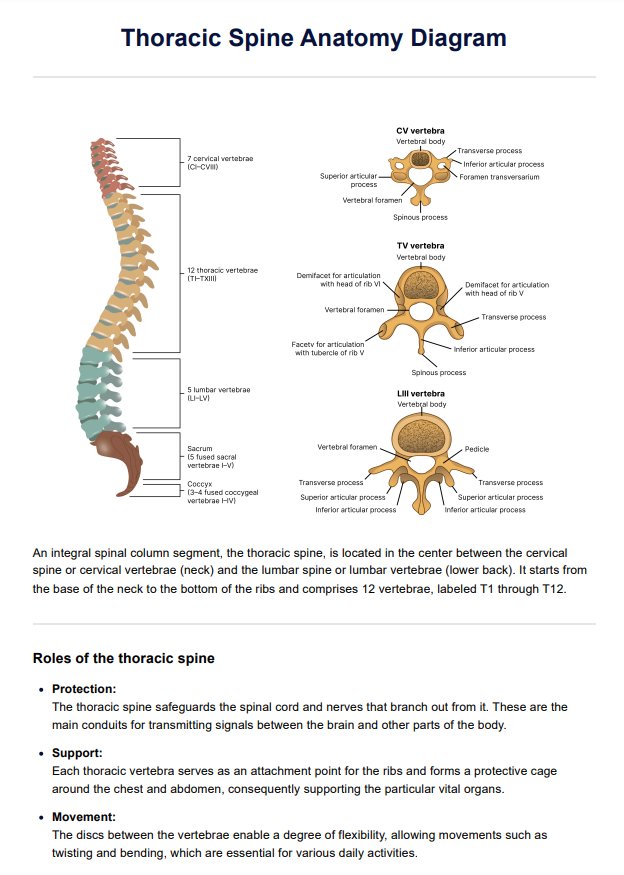

When medical professionals speak of radicular pain, they mean a type of pain that spreads. Radicular pain originates from the neck, hip, or back, travels along the spinal nerve root, and may turn into leg pain. It can be felt in areas like the anterior thigh, groin, calf, and even the foot, to mention a few.

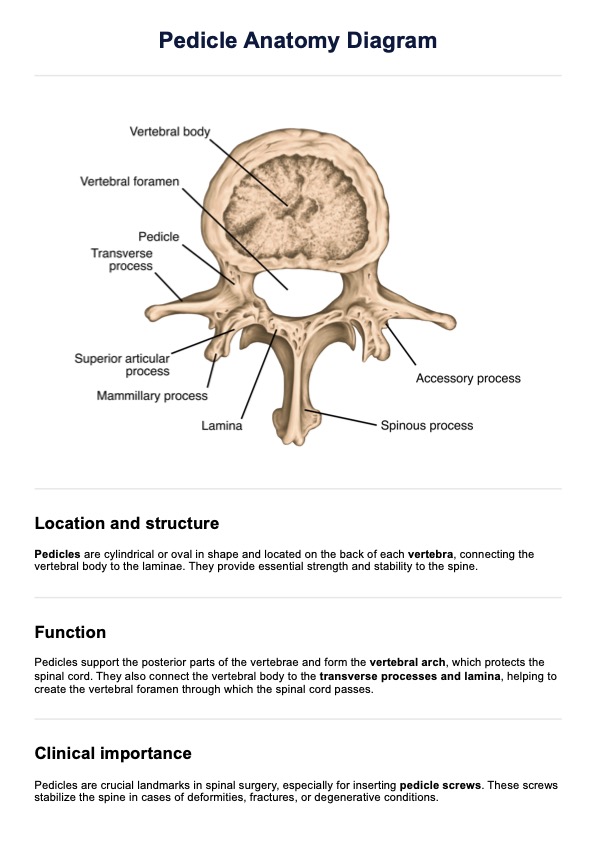

Radicular pain occurs because of a pinched nerve, specifically nerve roots in the spine, due to compression or irritation of the pinched nerve's root. This can happen in the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar regions. They will likely occur as a result of physical trauma due to falls or other accidents, the emergence of bone spurs, because of a herniated disc, or because of aging.

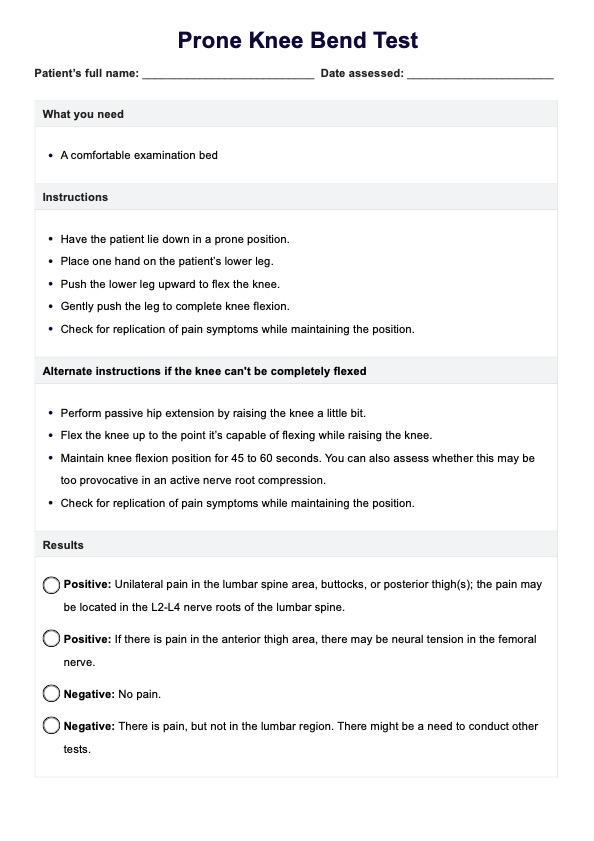

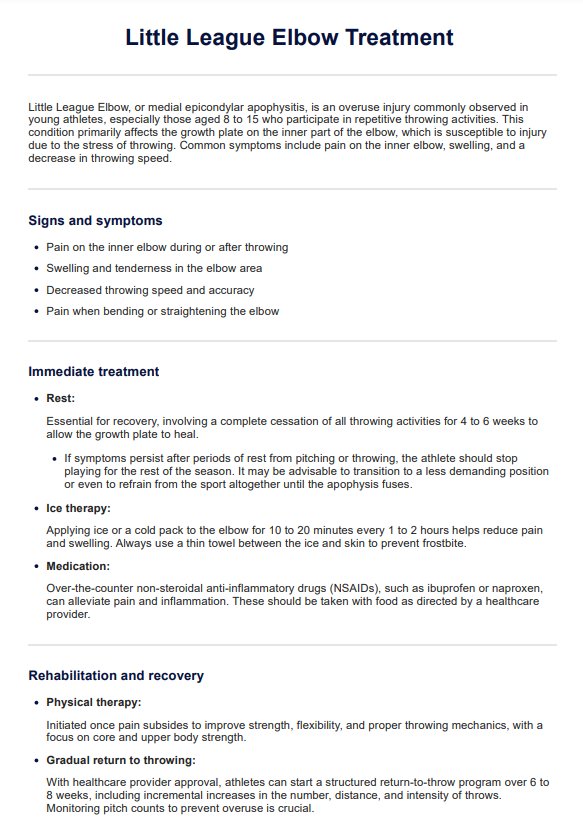

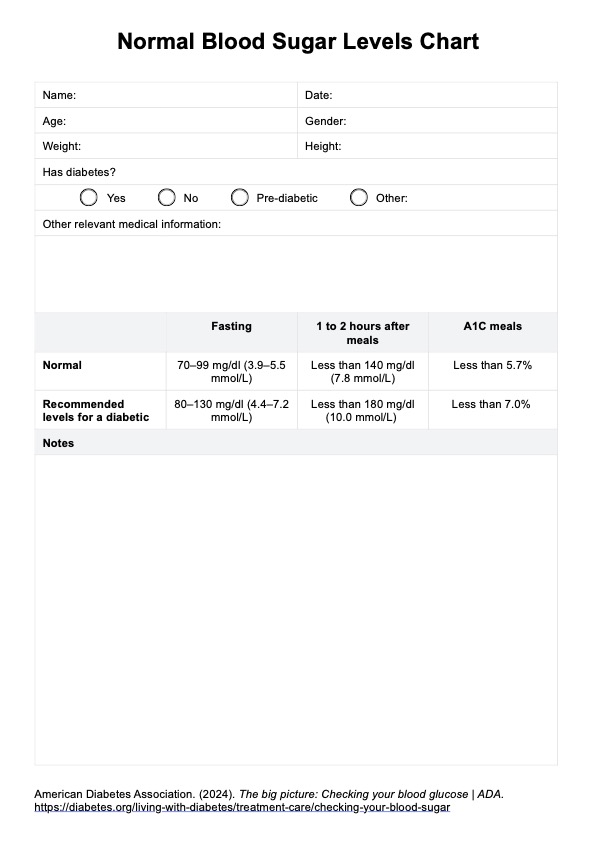

Prone Knee Bend Test Template

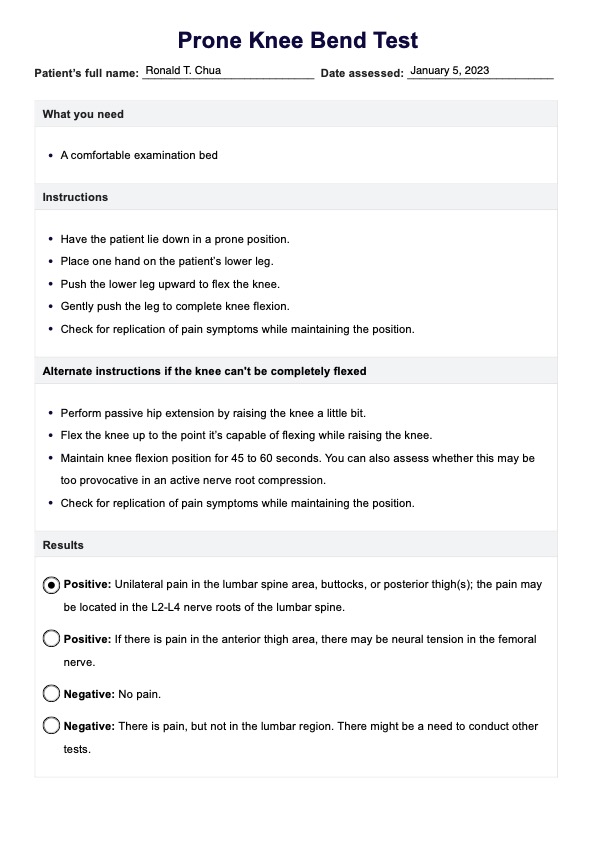

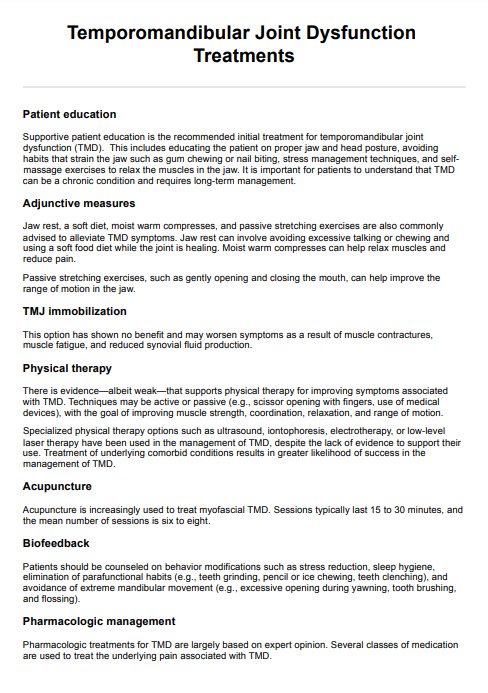

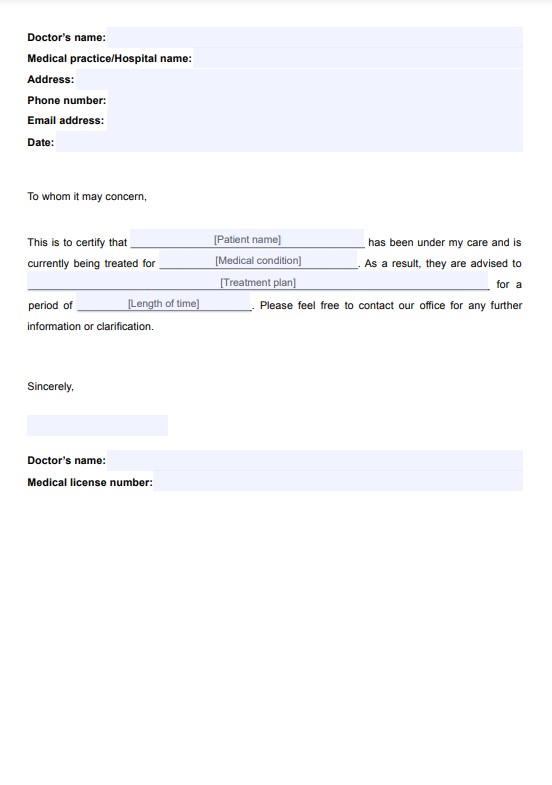

Prone Knee Bend Test Example

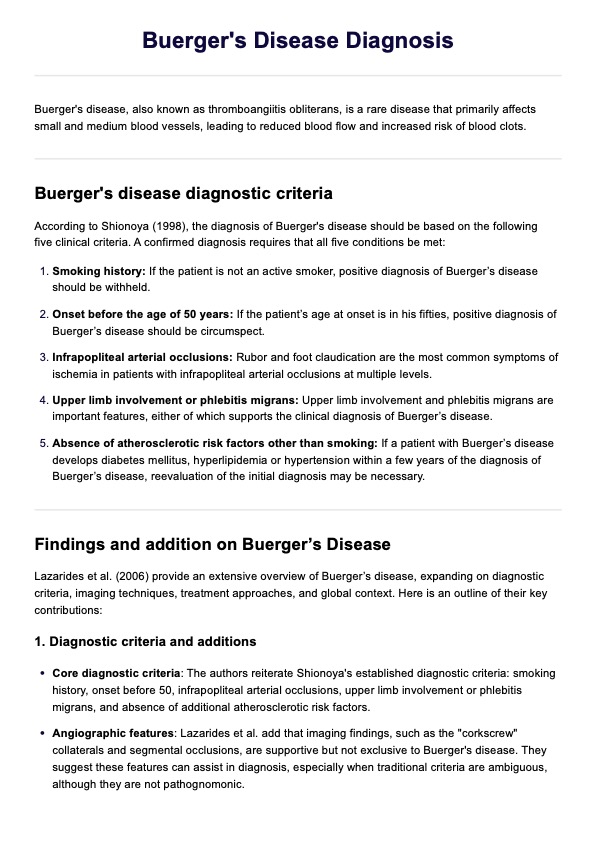

What is the Prone Knee Bend Test?

For this guide, we will focus on a test for assessing radicular pain in the lumbar region. It's called the Prone Knee Bend Test (sometimes called the femoral nerve stretch test or Reverse Lasègue Test). This neurodynamic test was created to determine whether the pinched nerve causing radicular pain is the femoral nerve in the lumbar region.

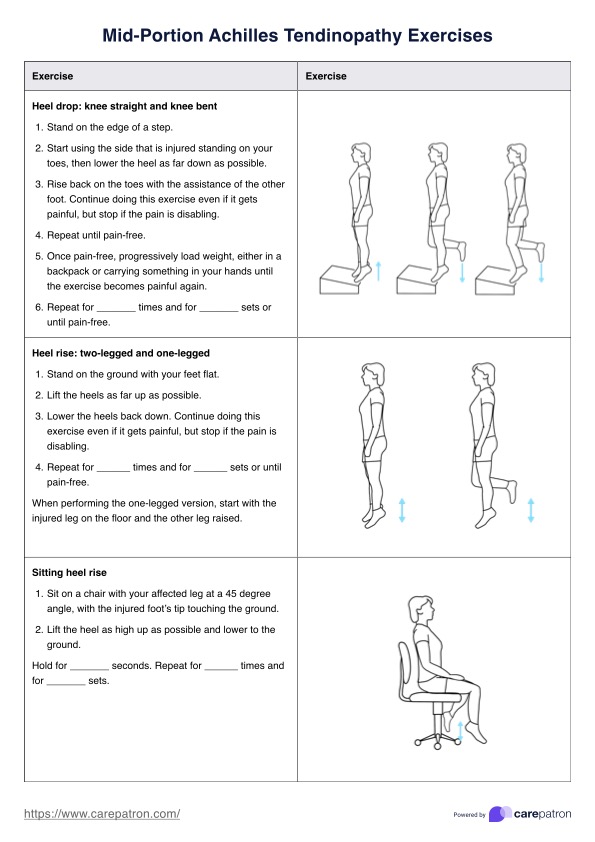

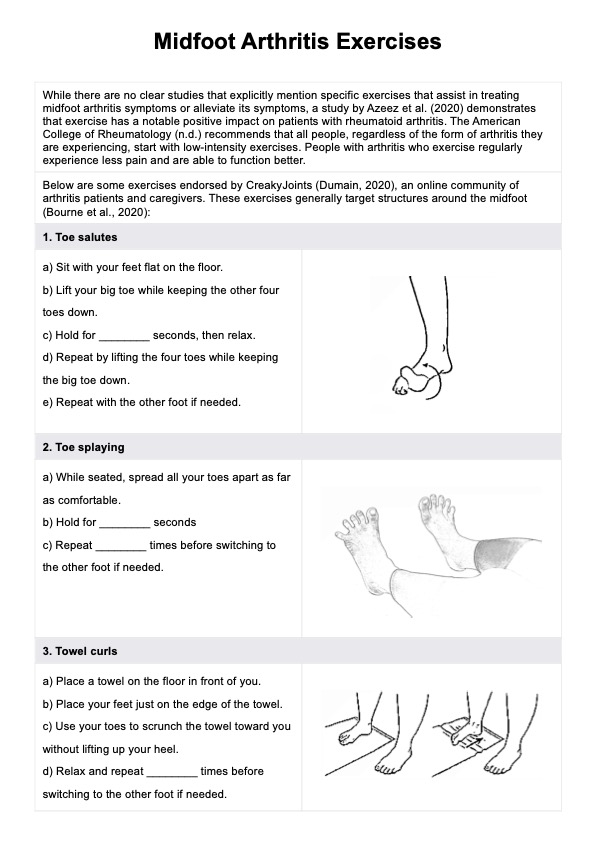

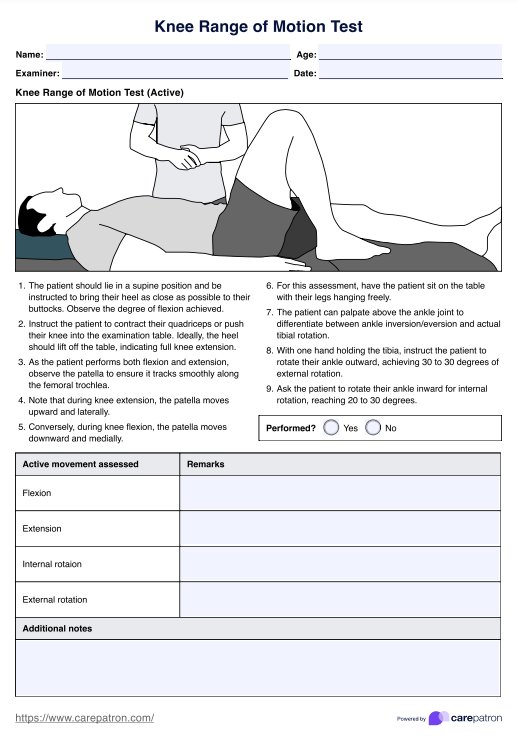

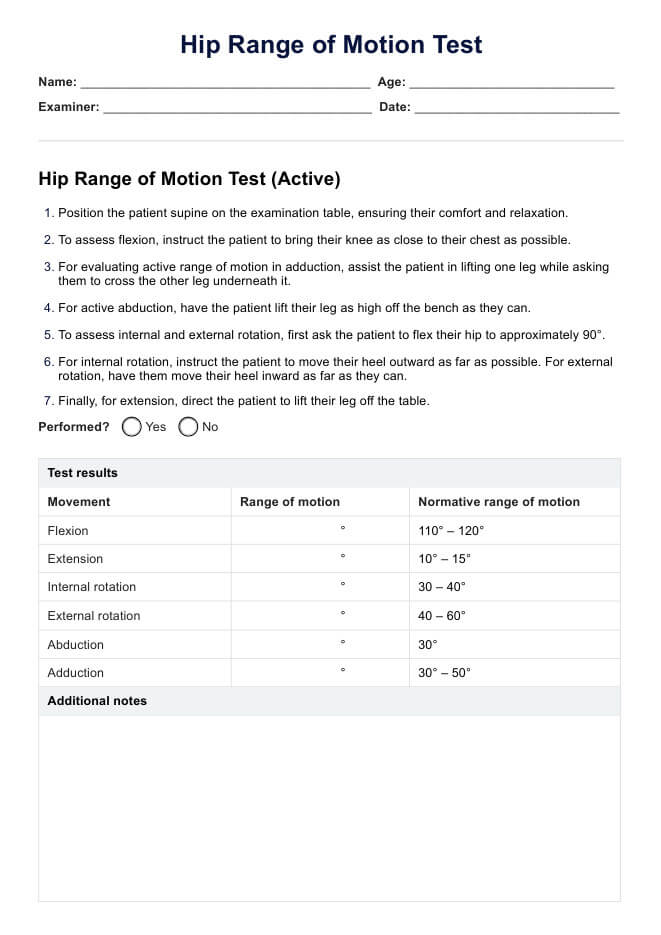

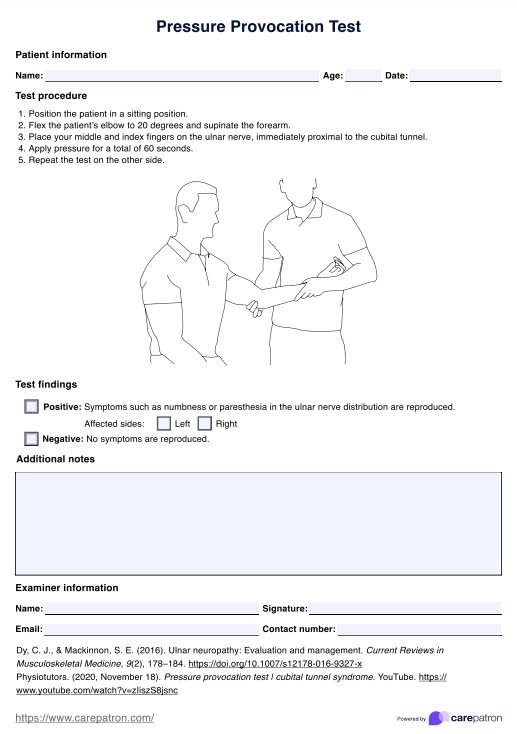

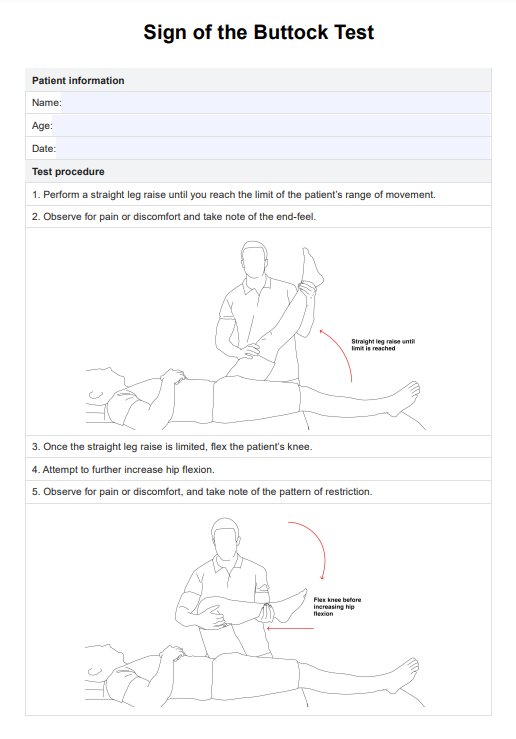

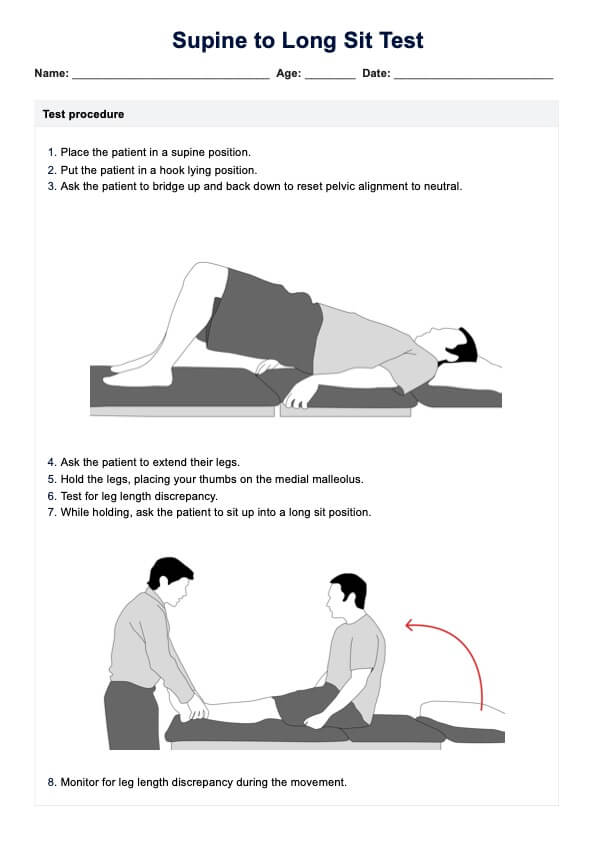

Before conducting this physical examination, the examiner must prepare an examination bed. The patient lies in a prone position for this test. Once the patient is in position, the examiner must place one hand on the patient's lower leg.

Next, the examiner passively forces the patient's knee into knee flexion and must gently push the knee to the end. Once the knee reaches the end of the flex, the examiner must maintain the position for 45 to 60 seconds. Throughout this time, the examiner should watch for the reproduction of the patient's symptoms of radicular pain.

If, for some reason, the knee can't be flexed completely, an alternate way of performing this neurodynamic test is to flex the knee as far as they can and then perform passive hip extension by raising the knee a bit. They also need to maintain this position for 45 to 60 seconds, which can be adjusted as this may be too provocative in an active nerve root compression. There should be no hip rotation (anterior rotation or otherwise).

How are the results of this test interpreted?

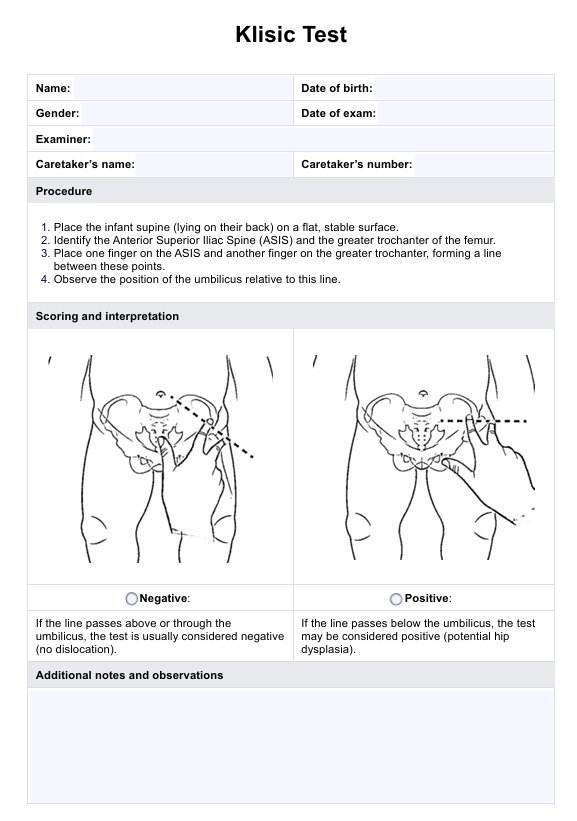

A positive test result can indicate the following possibilities:

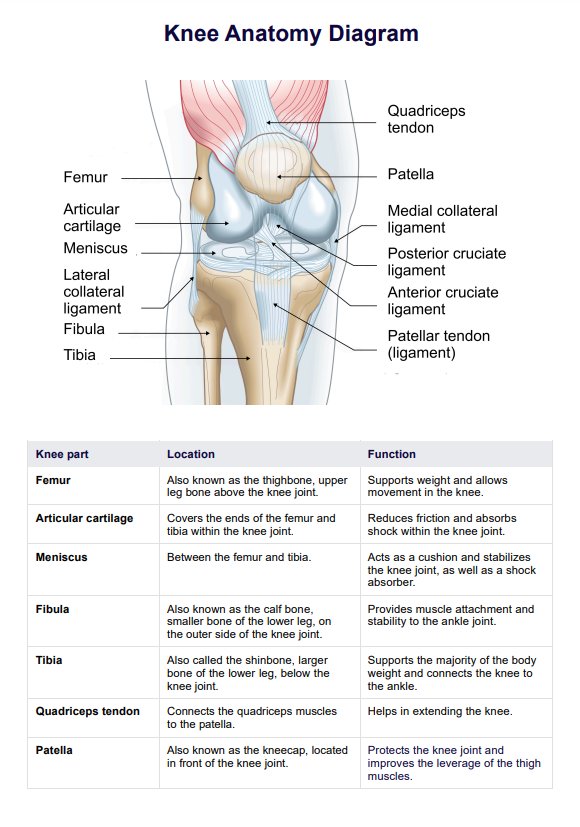

- If the patient feels unilateral pain in the lumbar spine area, their buttocks, or their posterior thigh(s), the pain may be located in the L2-L4 nerve roots of their lumbar spine. This can mean that there is an L2-L4 nerve root lesion.

- If the patient feels pain in the anterior thigh area, there may be neural tension in the femoral nerve. It can also mean their quadriceps muscle is strained or tight.

Please note that while a study on this test's diagnostic accuracy found a sensitivity of 50% and specificity of 100% (Suri et al., 2011), it should not be the one test to rely on. It merely detects the possible location of the radicular pain, specifically in the lumbar area.

It would be prudent to conduct another clinical test that involves hip flexors and the knee. The problem (e.g., potentially musculoskeletal disorders, upper lumbar radiculopathy, adverse neural tension) should also be confirmed through MRIs, CT scans, etc.

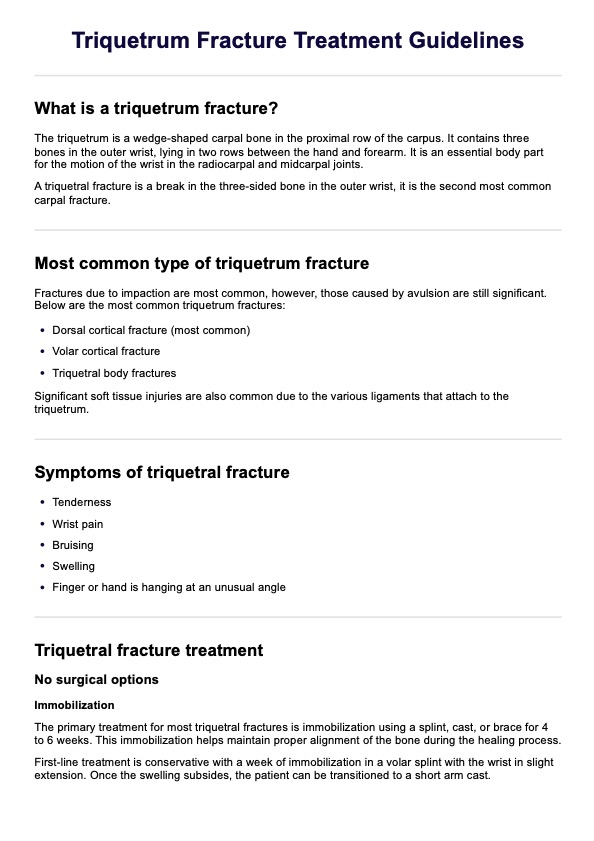

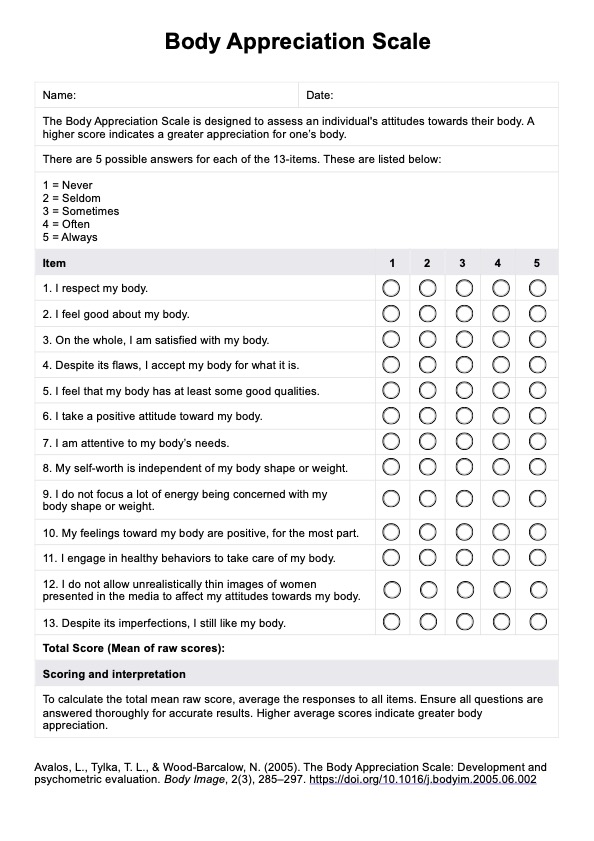

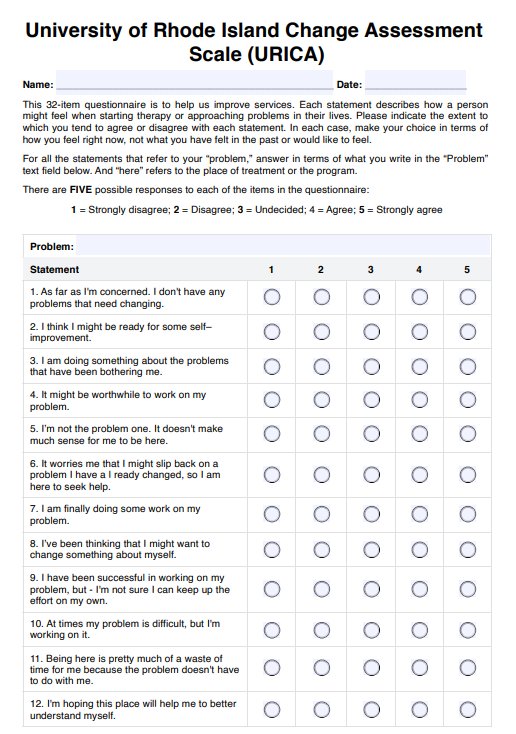

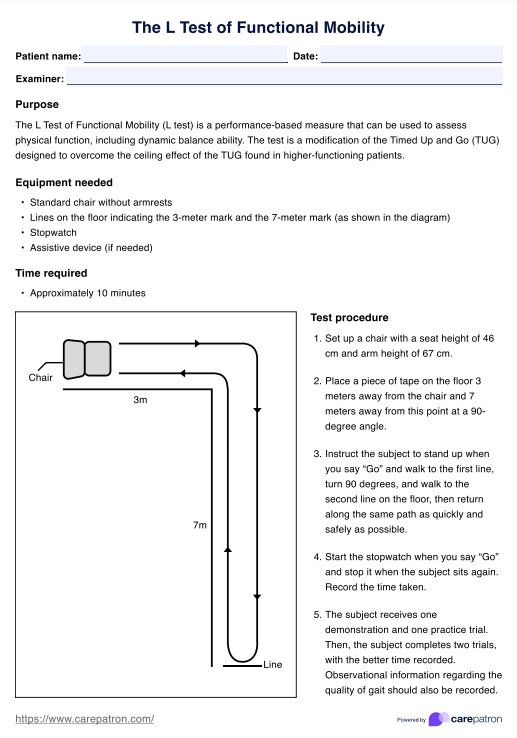

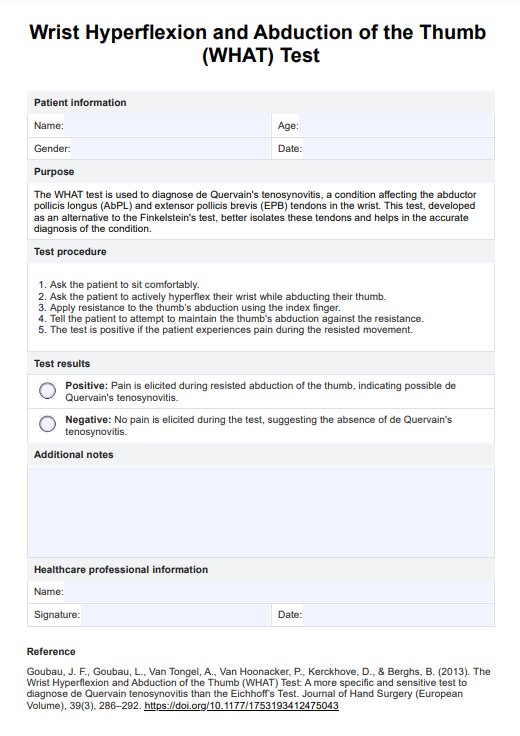

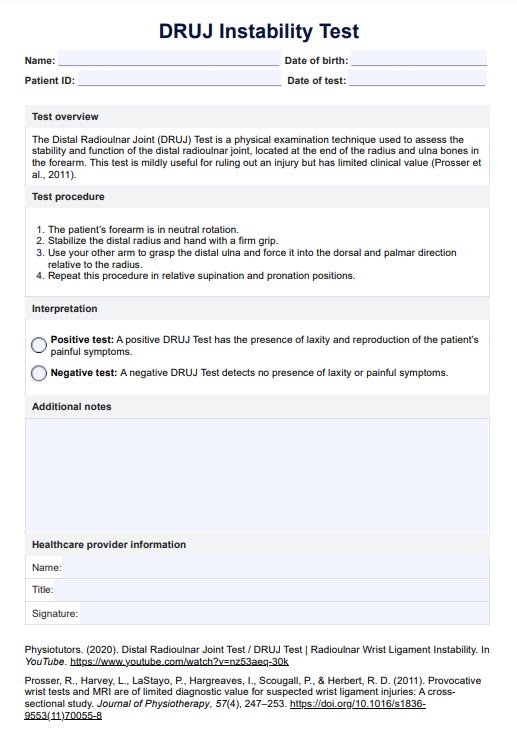

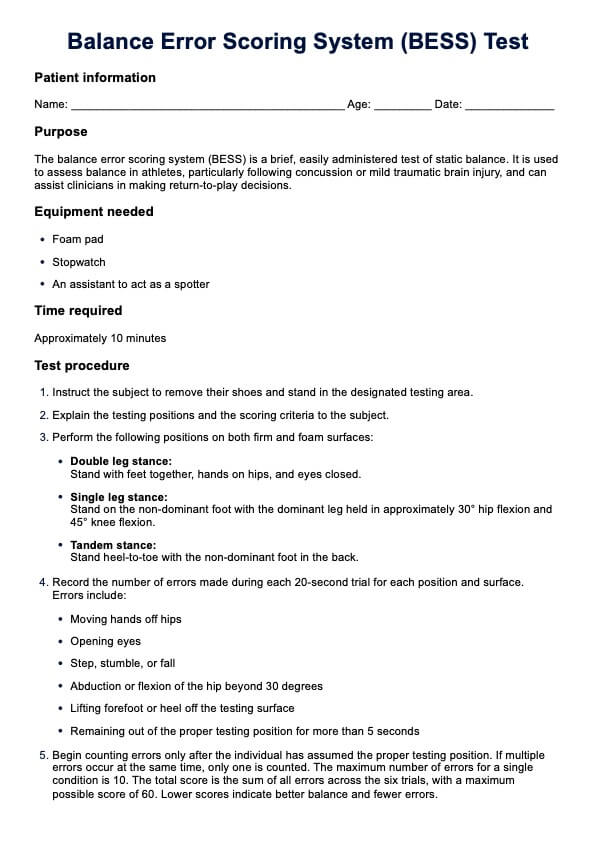

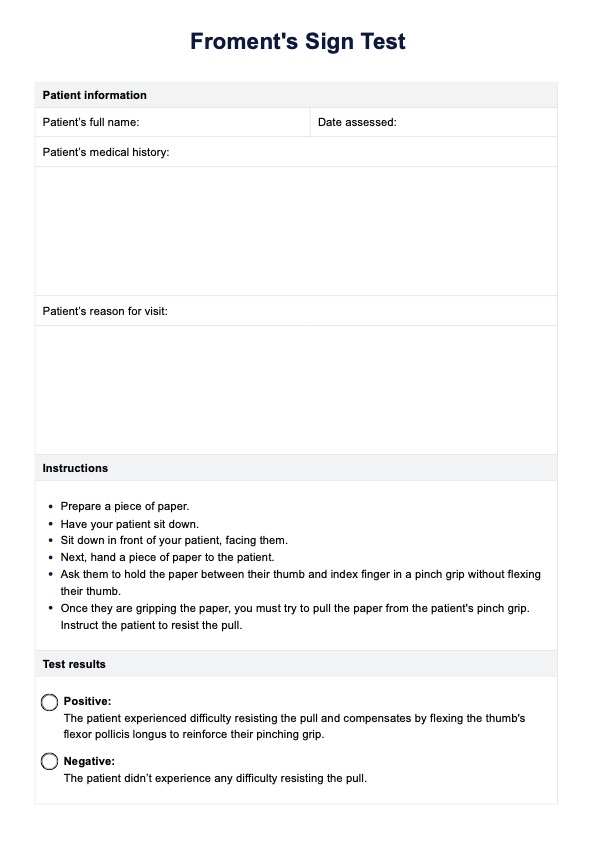

How does our Prone Knee Bend Test template work?

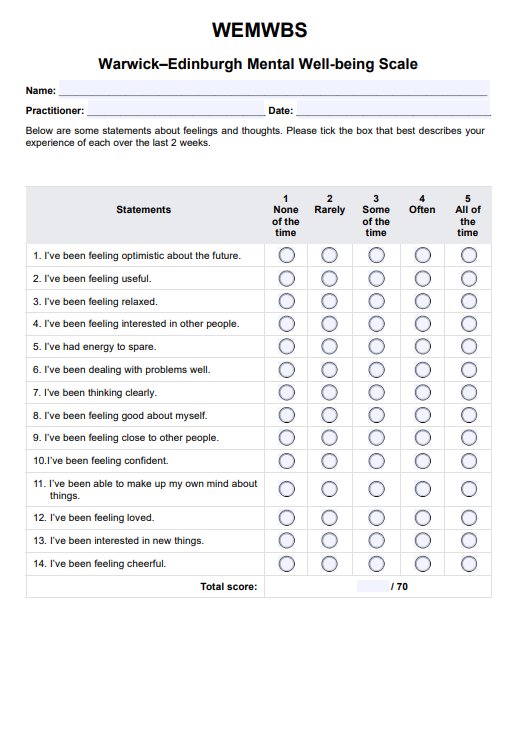

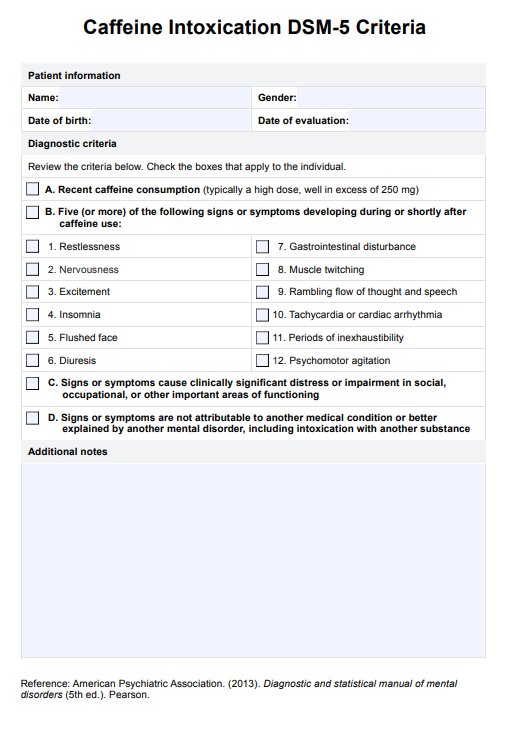

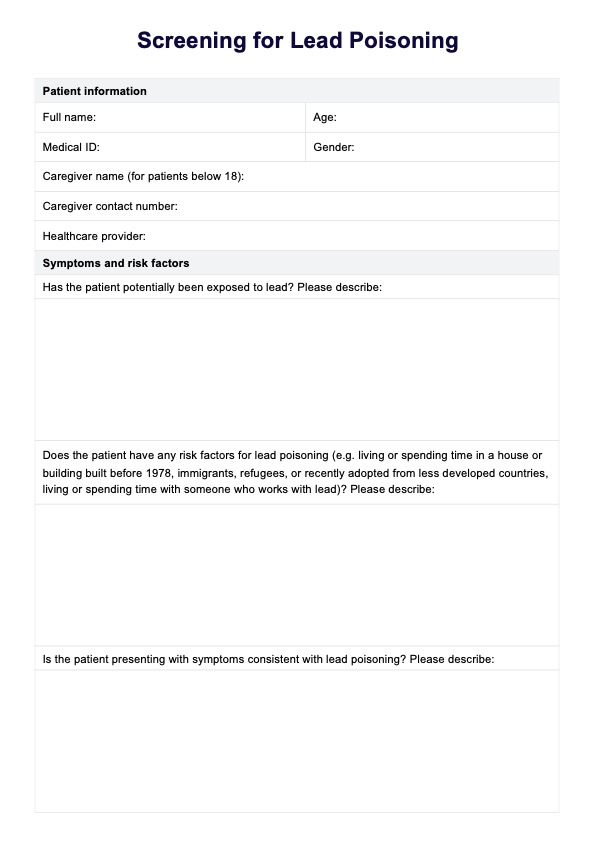

Usually, examinations such as the Prone Knee Bend Test don't have specific recording sheets to accompany them. We at Carepatron took the liberty to create a results recording template for this test to make it easier for neurologists, physical therapists, etc., to record their results.

The template asks these professionals to indicate their patient's name, medical history, feelings of radicular pain, and the date they underwent this test.

It also contains instructions on performing the test and four checkboxes to indicate whether it is positive or negative. There are two positive checkboxes. The professional must select the one based on the location of the pain. There are also two negative checkboxes—one indicating no pain and one indicating pain but not in the lumbar region.

You can also use the Slump Test template to evaluate neural tension and identify sources of nerve-related pain. The Straight Leg Raise Test template is useful for assessing lumbar nerve root involvement and detecting herniated discs. The Thomas Test template also helps assess hip flexor tightness and differentiates between various causes of hip and lower back pain.

What are the benefits of this test?

Here are some of the benefits of using our Prone Knee Bend Test template:

It's easy and quick to conduct

One of the great things about neurodynamic tests, such as the Prone Knee Bend Test, is that they don't require much to be conducted. All this test needs is an examination bed and the examiner's two hands to conduct. The instructions are nowhere near complicated, and the test can be completed in two minutes.

It can help narrow down the source of a person's radicular pain

Before anything, it's best to remember that this test is not diagnostic, mainly because it doesn't confirm the problem. It confirms the location of the radicular pain, and knowing its location can help narrow down the potential issues causing it. It's also a good fit for comprehensive physical examinations because it can work well with other neurodynamic examinations to determine the potential sources of radicular pain.

It can be used as a monitoring test

Let's stipulate that an official diagnosis is made. The patient is confirmed to have a femoral nerve lesion. A professional can schedule a routine physical examination to check if the pain is still there and if it's improving. One way of doing so is to reconduct the Prone Knee Bend Test. If the pain is still there and still hurts to the same degree as before, perhaps tweaking a patient's treatment plan is best.

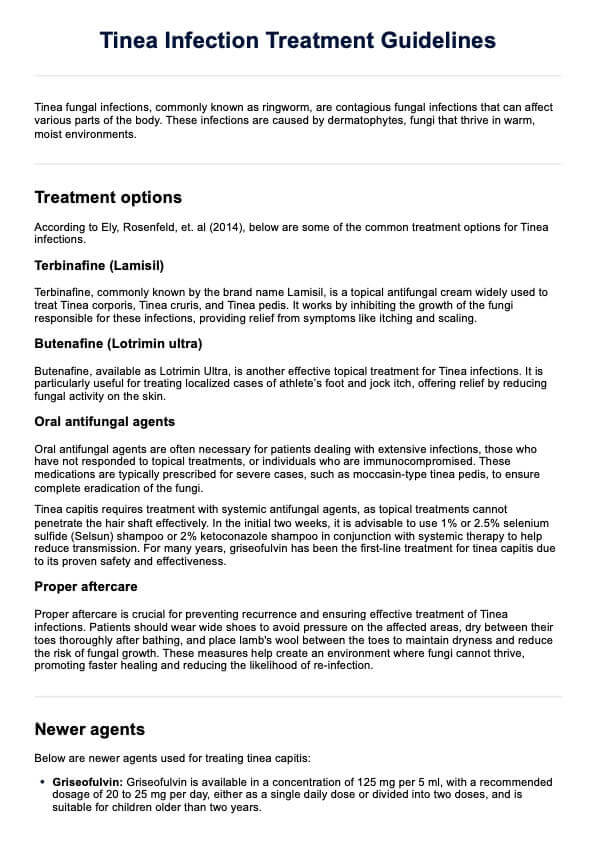

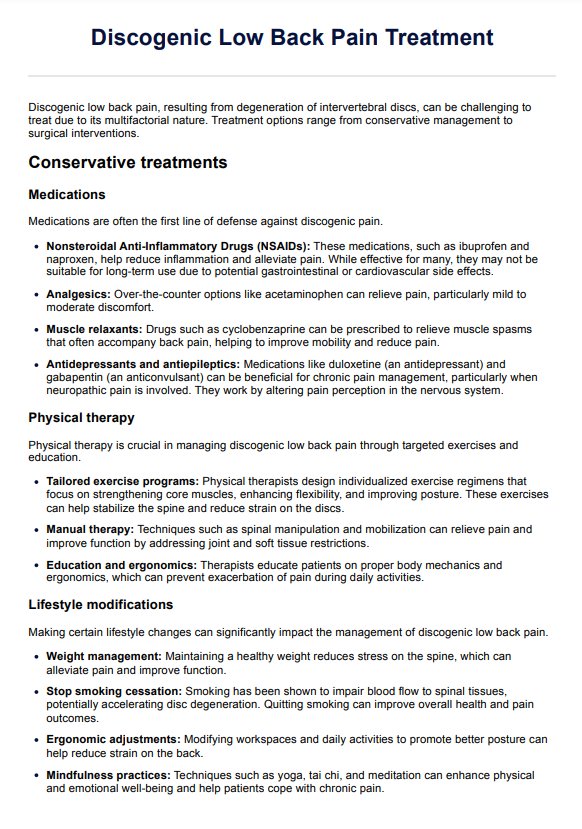

Radicular pain treatments

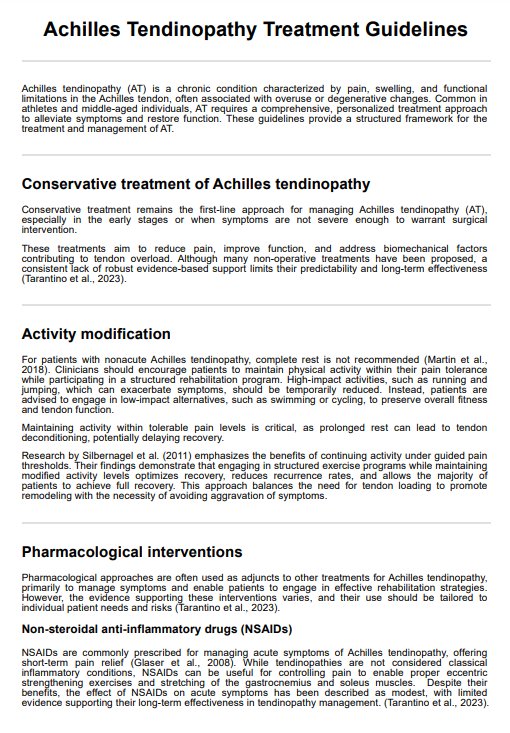

Radicular pain treatments vary depending on the severity of the condition and its underlying cause. Some treatments are more conservative:

Using ice or heat compress

This is the most conservative way to treat radicular pain. Ice or heat compresses will help soothe the muscles in the back, which can relax and untighten them. Using compresses may even reduce swelling. How often and long such compresses should be used depends on a patient's discussions with their healthcare provider.

Using pain relievers

If an ice or heat compress isn't working, healthcare professionals are likely to prescribe over-the-counter NSAIDs to relieve the pain. It would be best to follow the recommended dosage and number of days they should be taken. Another option is to take corticosteroids, which come in the form of pills or injections. Like NSAIDs, these should also relieve the pain.

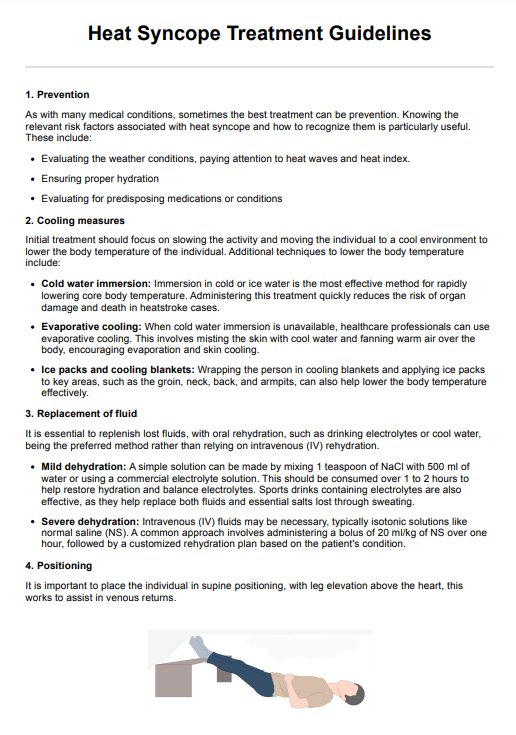

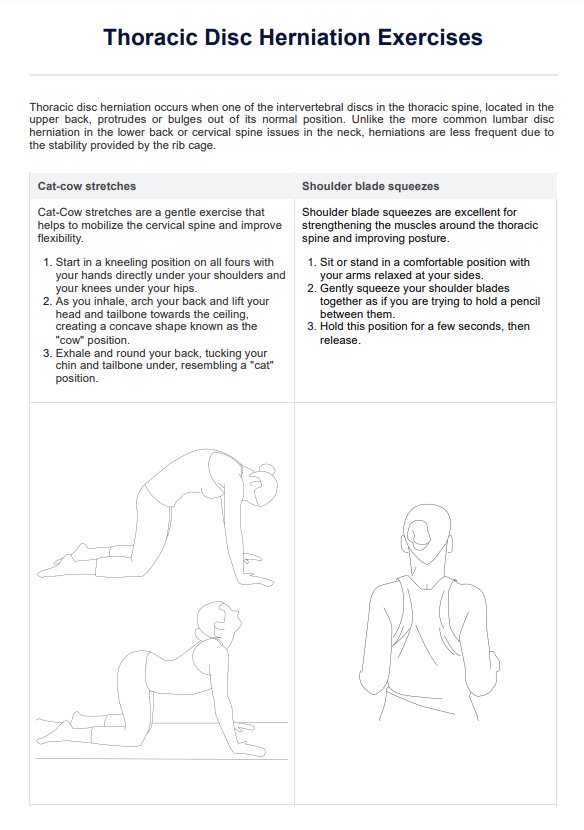

Taking physical therapy

Physical therapy can help relieve radicular pain over time by having the patient participate in simple exercises to relieve spinal pain. Not only will such exercises ease pain, but they can also help with fixing posture. Whatever exercises a patient will take will depend on what their therapist believes is right for them.

Reference

Suri, P., Rainville, J., Katz, J. N., Jouve, C., Hartigan, C., Limke, J., Pena, E., Li, L., Swaim, B., & Hunter, D. J. (2011). The accuracy of the physical examination for the diagnosis of midlumbar and low lumbar nerve root impingement. Spine, 36(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c953cc

Commonly asked questions

Surgery for radicular pain is rare. The only time this becomes an option is if all other forms of treatment don't work and if the pain is severe, so it would be best to resort to more conservative methods first, like lumbar spinal extension exercises.

Some people lose their radicular pain in a few days, and some take a few weeks. If radicular pain lasts for months, it is best to see a healthcare professional as soon as possible.

The most basic way to prevent radicular pain is to maintain good spine posture and avoid situations that can lead to accidents impacting your spinal cord.