Key components of a Pediatric Assessment

A comprehensive Pediatric Assessment involves several key components designed to evaluate the child’s overall health and development. Each part plays a vital role in identifying the patient's illness, monitoring growth, and guiding early intervention.

Factors such as birth history, family history, medical history, and the chief complaint help tailor the assessment based on the child’s developmental stage and developmental level. Understanding the child’s eye contact, work of breathing, and child’s interaction with caregivers further supports further investigation when abnormalities arise.

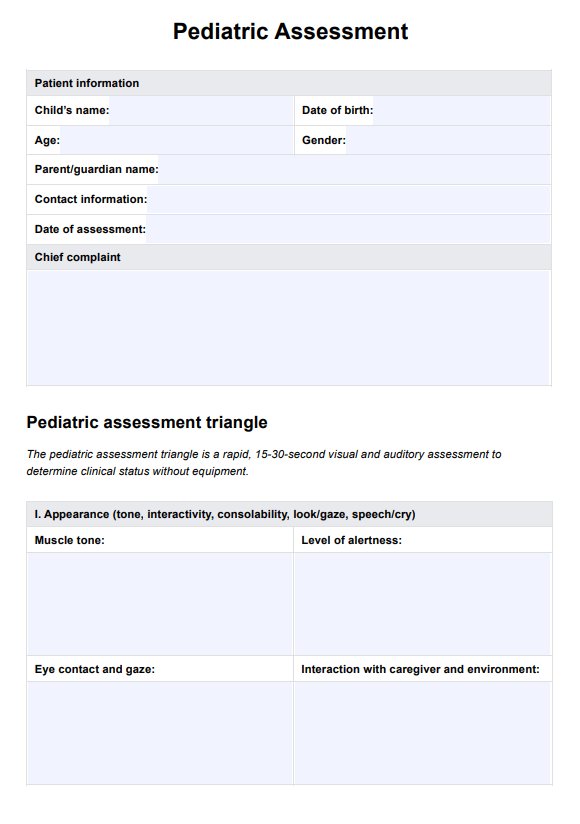

Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT)

The Pediatric Assessment triangle (PAT) is a rapid, non-invasive tool used to assess a child’s clinical status within 15-30 seconds (Horeczko et. al., 2013). It evaluates appearance, work of breathing, and circulation to the skin without specialized equipment. The appearance focuses on the child’s tone, consolability, and eye contact, which helps determine the developmental stage and potential neurological concerns.

The work of breathing component assesses retractions, nasal flaring, and abnormal breath sounds, critical for detecting respiratory distress. Circulation evaluation includes skin color and capillary refill to identify perfusion issues. PAT is particularly useful in emergency settings for small children who may not verbalize symptoms, providing an immediate snapshot of severity and guiding further investigation and treatment priorities.

Comprehensive physical/occupational therapy assessment

A comprehensive physical and occupational therapy assessment evaluates a child’s developmental level, motor skills, sensory processing, and ability to perform age-appropriate tasks. It begins with reviewing the birth history, birth weight, and medical history to understand underlying factors influencing development.

Evaluating children’s ability to complete tasks such as dressing, feeding, and mobility helps identify delays requiring early intervention. For older children, assessments focus on coordination, strength, and daily functioning. Therapists observe the child’s interaction with the environment, noting signs like stranger anxiety or abnormal motor patterns.

Pain assessments, including the child’s pain scale, and monitoring vital signs like temperature and blood pressure (compared to the normal range for the child’s age) provide insight into functional limitations. This comprehensive approach ensures individualized treatment planning to promote independence and address developmental concerns.