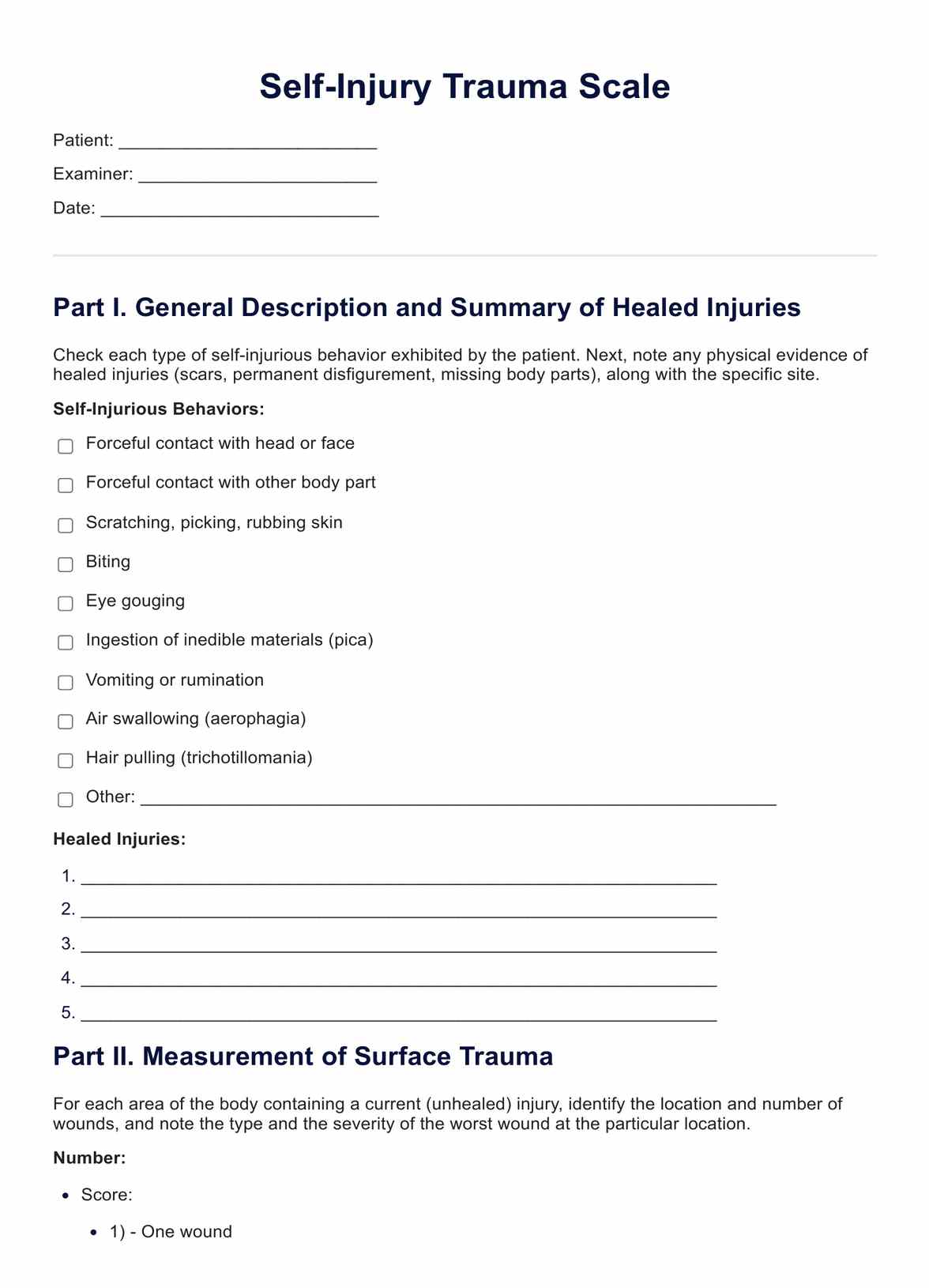

Self Injury Trauma Scale

Explore the Self Injury Trauma Scale: Understanding, assessing, and navigating the path to healing from self-harm and associated trauma.

An introduction to trauma

Trauma, in the medical context, encompasses a broad spectrum of physical and psychological injuries resulting from a wide array of incidents. The classification of trauma is not limited to the stereotypical disaster events, attacks, or accident scenarios, but extends to encompass any event that overwhelms an individual's ability to cope. Understanding trauma involves recognizing its diverse manifestations and understanding the links between the mind, body, and environment.

Physical trauma often refers to injuries sustained due to external forces, such as falls, accidents, or violence. These injuries can range from minor cuts and bruises to severe fractures, head injuries, or damage to internal organs. The severity of physical trauma varies, and its impact may extend beyond the immediate injury, influencing long-term health outcomes.

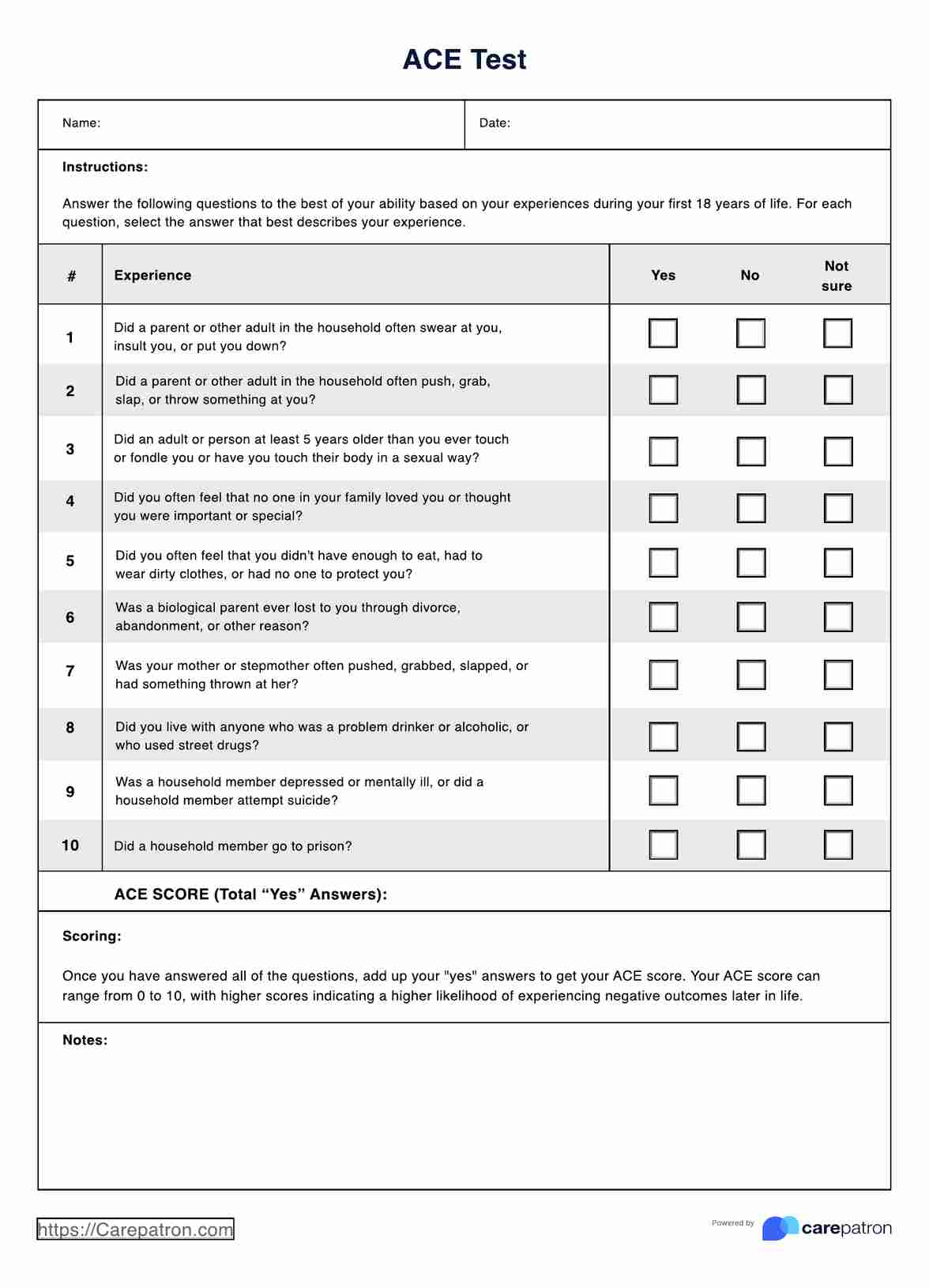

Psychological trauma, on the other hand, involves the emotional and mental toll of distressing events. This can result from experiences such as abuse, neglect, accidents, natural disasters, or witnessing violence. Psychological trauma can lead to a range of emotional responses, including shock, anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The effects of psychological trauma may persist long after the triggering event, influencing an individual's mental well-being and overall quality of life.

In some cases, trauma involves a combination of physical and psychological elements, creating a complex interplay of challenges for individuals and healthcare professionals alike. The body's response to trauma, known as the stress response, involves intricate physiological changes aimed at survival. However, prolonged or intense stress responses can contribute to the development of chronic health conditions and exacerbate existing medical issues.

Healthcare providers must approach trauma with a holistic perspective, recognizing the interconnectedness of physical and psychological aspects. The field of trauma medicine emphasizes not only the treatment of immediate injuries but also the consideration of long-term consequences and the provision of comprehensive care to support recovery.

Understanding trauma involves acknowledging its subjective nature. What may be traumatic for one individual might not be for another. Factors such as resilience, pre-existing mental health conditions, and social support systems play pivotal roles in determining an individual's response to trauma.

Healthcare providers addressing trauma require a multidisciplinary approach, integrating physical and mental health interventions to promote comprehensive healing. Recognizing the pervasive impact of trauma within healthcare settings allows for more empathetic and effective patient care, fostering a collaborative environment for recovery and resilience.

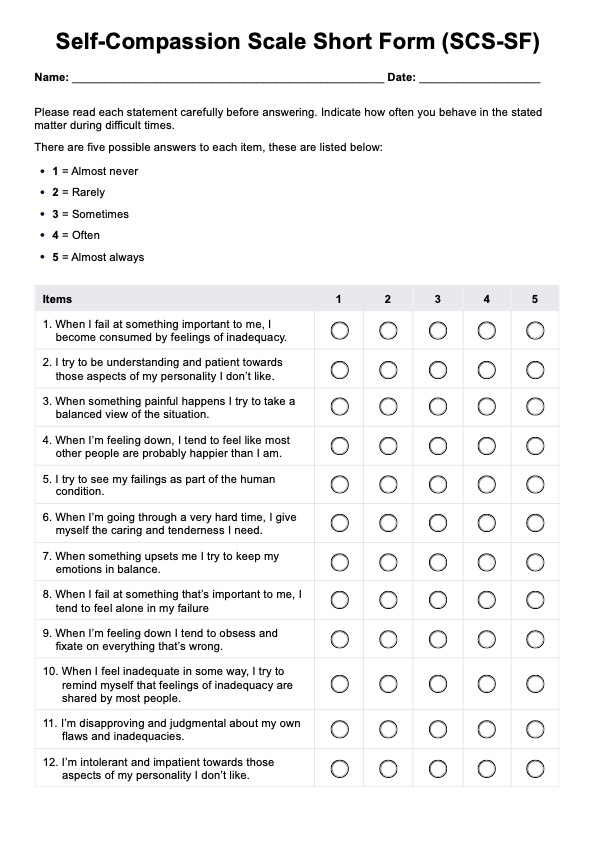

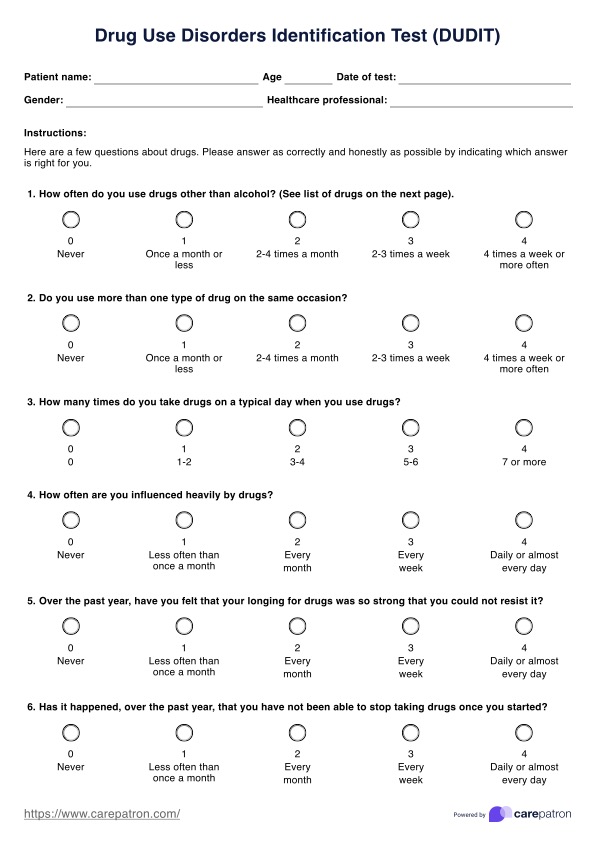

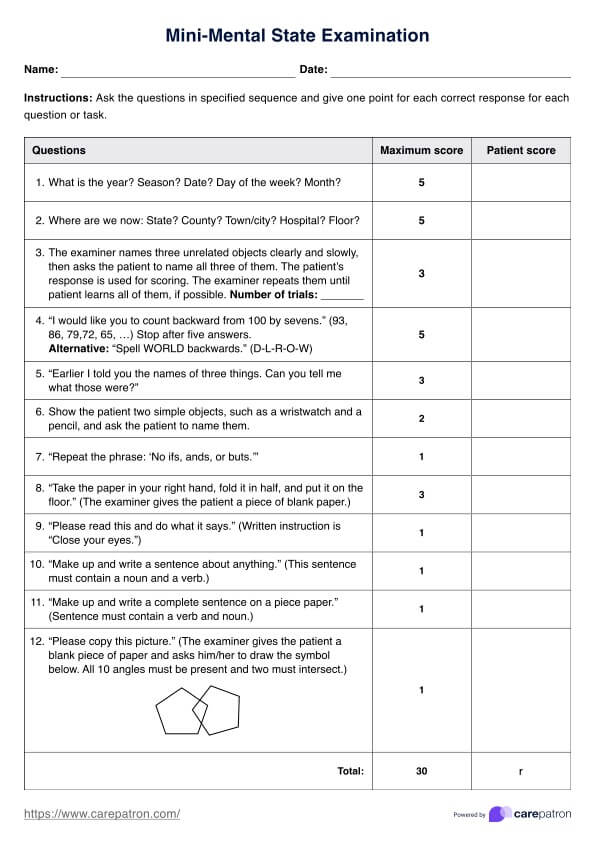

Self Injury Trauma Scale Template

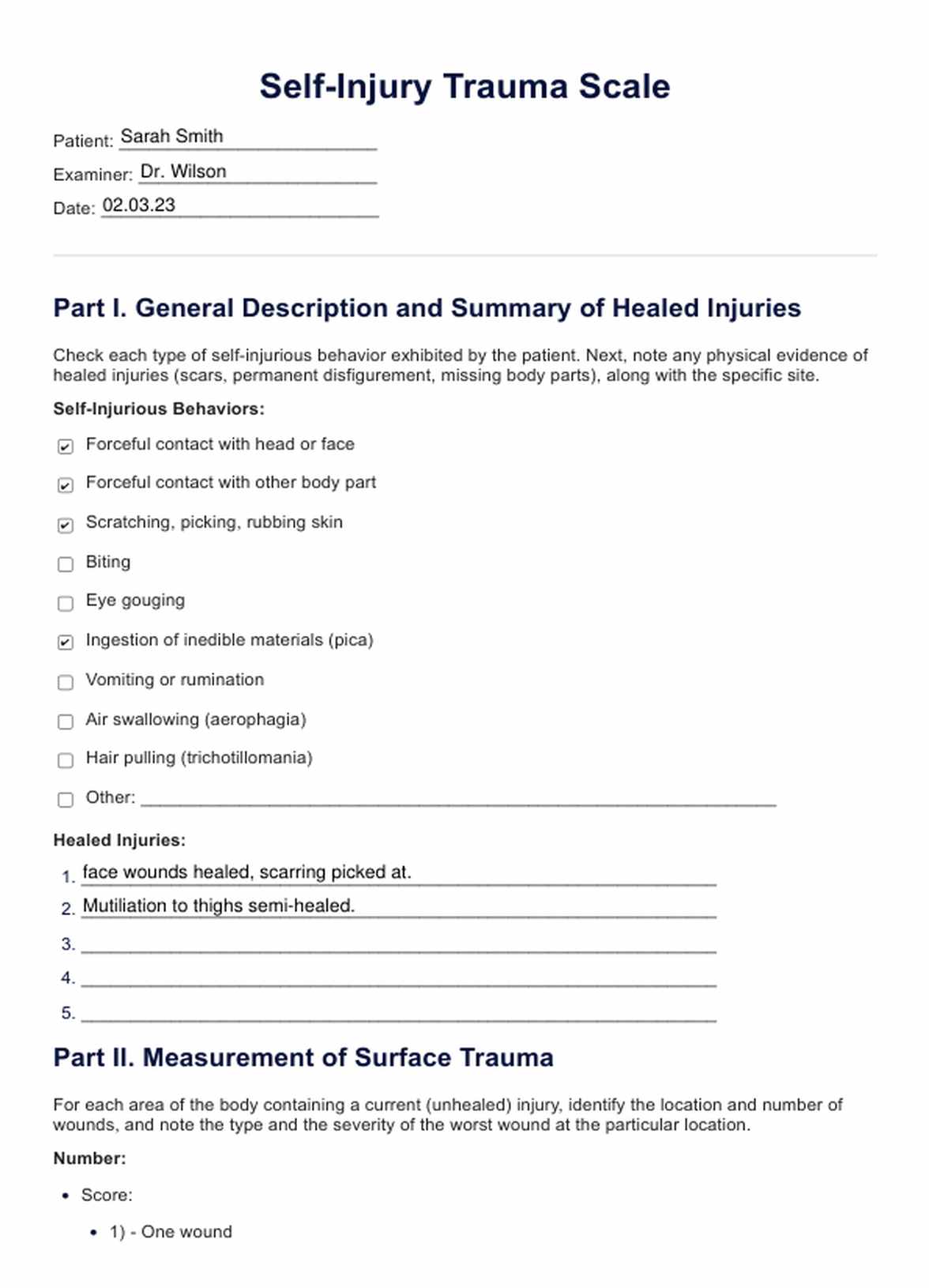

Self Injury Trauma Scale Example

Trauma and self-injury

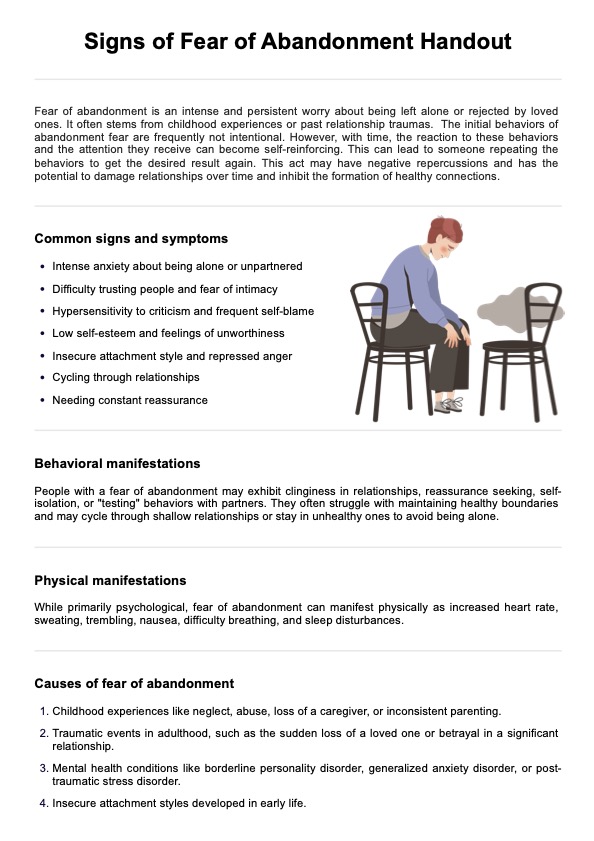

From a psychological perspective, the link between trauma and self-injury is intricate and rooted in the complex ways individuals cope with overwhelming emotional pain. Trauma, defined as the emotional and psychological response to distressing events that exceed one's ability to cope, can lead to a range of adverse outcomes, and self-injury often emerges as a maladaptive coping mechanism in the aftermath of trauma. The links between trauma and self-injury are outlined below:

Coping mechanism

Individuals who have experienced trauma may struggle with overwhelming emotions, memories, or a pervasive sense of distress. Self-injury, such as cutting or burning, can serve as a way to cope with these intense feelings. The physical pain resulting from self-injury may provide a temporary distraction from emotional pain or a tangible expression of inner turmoil.

Regulation of emotions

Trauma can disrupt emotional regulation, making it challenging for individuals to manage their feelings effectively. Self-injury may serve as a means of regaining a sense of control over emotions, offering a momentary reprieve from emotional chaos. The act of self-harm can create a tangible, visible expression of internal pain that may be otherwise difficult to articulate.

Expression of unspoken pain

Trauma often involves experiences that are difficult to put into words. Self-injury can become a non-verbal language for expressing pain, providing an outlet for emotions that feel overwhelming or inexpressible. The physical wounds may symbolize the unseen wounds of trauma, allowing individuals to externalize their internal struggles.

Self-punishment and guilt

Some individuals who have experienced trauma may harbor feelings of guilt, shame, or self-blame. Self-injury can become a way to punish oneself or a method of externalizing internalized negative emotions. It may be an unconscious attempt to cope with feelings of unworthiness or to seek relief from overwhelming guilt associated with the traumatic event.

Control and empowerment

Trauma can leave individuals feeling a profound loss of control. Engaging in self-injury may paradoxically provide a sense of control and agency, allowing individuals to dictate the extent and nature of their pain. In this way, self-injury becomes a way to reclaim a modicum of control in the aftermath of traumatic experiences.

Understanding the link between trauma and self-injury is crucial for mental health professionals working with individuals who engage in self-harming behaviors. Effective treatment involves addressing the underlying trauma, developing healthier coping mechanisms, and fostering resilience to reduce reliance on self-injury as a maladaptive strategy for managing emotional pain.

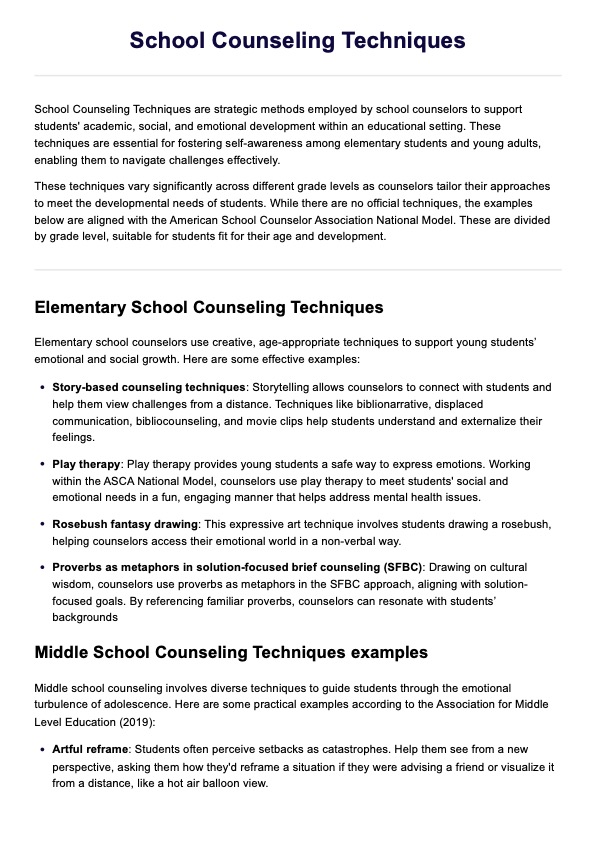

Signs and symptoms your patient is engaging in self-injurious behavior

Recognizing signs and symptoms of self-injurious behavior in a patient is crucial for healthcare professionals to provide appropriate support and intervention. While not exhaustive, the following list outlines common indicators that an individual may be engaging in self-harming behaviors:

Unexplained cuts, bruises, or burns

Visible injuries, particularly when inconsistent with the individual's explanation, may be indicative of self-inflicted harm. Regularly noticing unexplained wounds, especially in concealed areas, should raise concern.

Frequent wearing of concealing clothing

Individuals engaging in self-injurious behavior may wear clothing that conceals their body, even in warm weather. Long sleeves or pants may be worn to hide scars or fresh injuries.

Isolation and withdrawal

Increased social withdrawal or isolation may be a sign that the individual is struggling with emotional pain. They may avoid activities or situations that would typically bring them joy or engage in increased solitude.

Emotional instability

Frequent and intense mood swings, emotional outbursts, or expressions of hopelessness can be indicators of underlying emotional distress. Sudden shifts in behavior or demeanor may suggest the presence of self-harming behaviors.

Difficulty in relationships

Strained interpersonal relationships, conflicts with family or friends, and difficulty in forming or maintaining connections could be linked to the emotional challenges associated with self-injury.

Evidence of self-harm tools

Discovering items such as razors, knives, or other sharp objects in the individual's belongings may suggest a risk of self-injurious behavior. The presence of these tools should be approached with concern.

Frequent excuses or unconvincing explanations

Individuals may offer vague or inconsistent explanations for injuries, dismissing them as accidents. Pay attention if these explanations seem improbable or change frequently.

Preoccupation with pain or death

Expressing a preoccupation with themes of pain, death, or self-harm in conversation, art, writing, or online activities may signal an individual's internal struggles.

Secretive behavior

Engaging in secretive or ritualistic behaviors, such as frequent bathroom visits or insistence on privacy, may be an indication of self-injurious activities.

Increased substance abuse

Substance abuse can be intertwined with self-injury as individuals may use drugs or alcohol to cope with emotional pain. An escalation in substance use should be noted.

It's important to approach the identification of self-injurious behavior with sensitivity and empathy. If healthcare professionals or concerned individuals notice these signs, engaging in open and non-judgmental communication is advisable, encouraging the individual to seek professional help. Prompt intervention and support can be pivotal in guiding the individual toward healthier coping mechanisms and psychological well-being.

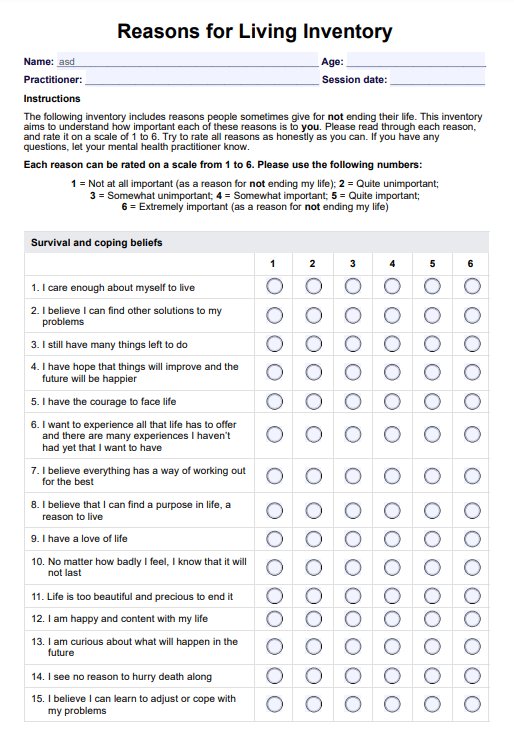

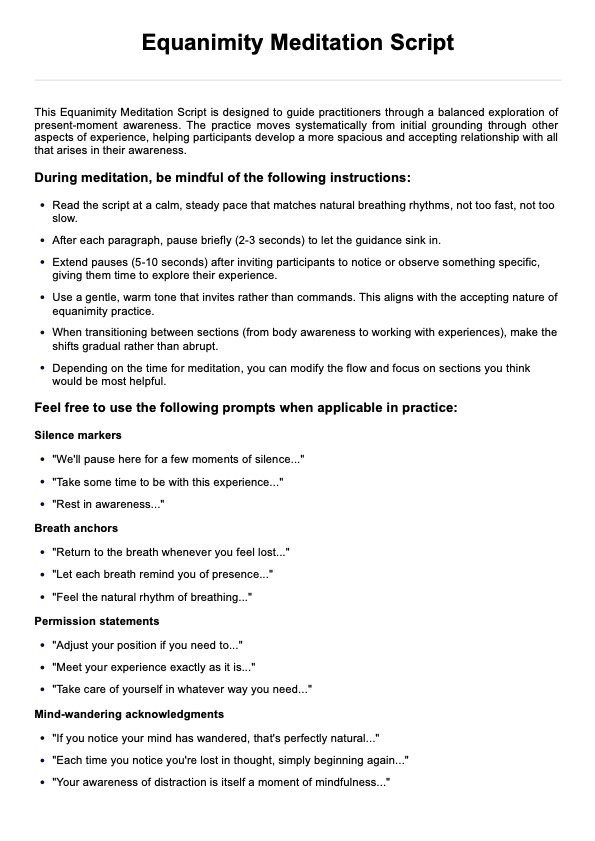

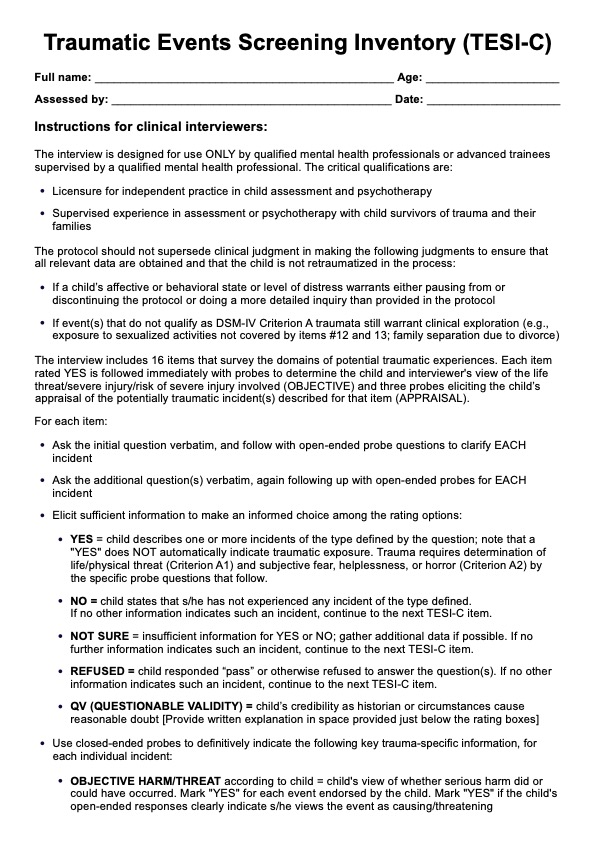

When should this scale be applied?

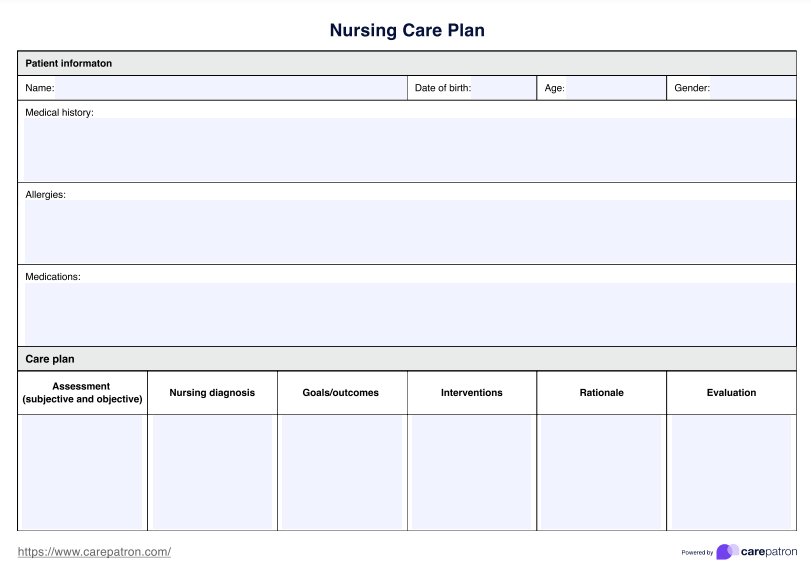

The Self-Injury Trauma Scale (SIT Scale) is a clinical tool designed to assess the impact of self-injurious behavior on individuals who engage in self-harm. It is typically used by mental health professionals, such as psychologists, psychiatrists, or counselors, to gather information about the severity and consequences of self-injury. The application of the SIT Scale may be considered in various clinical contexts, including:

Initial assessment

Mental health professionals may use the SIT Scale during the initial assessment of individuals who disclose a history of self-injury or present with self-inflicted wounds. This can help gather baseline information about the nature and extent of the self-harming behaviors.

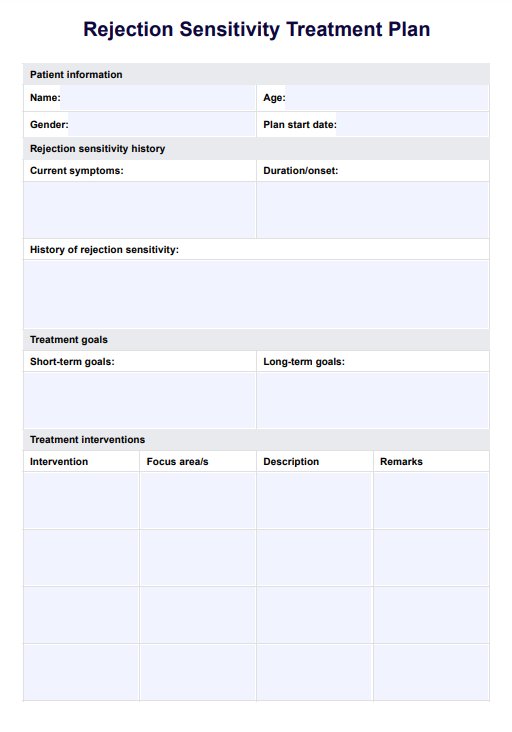

Treatment planning

The SIT Scale can be employed as part of the treatment planning process. By assessing the trauma associated with self-injury, mental health professionals can tailor interventions and therapeutic approaches to address the specific needs and challenges faced by the individual.

Follow-up and progress monitoring

Periodic administration of the SIT Scale allows mental health professionals to monitor changes in self-injurious behavior over time. This ongoing assessment can help gauge the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions and identify areas that may require further attention.

Crisis intervention

In situations where individuals are in crisis or experiencing acute distress related to self-injury, the SIT Scale can provide a structured framework for understanding the immediate impact of the behavior. This information can guide crisis intervention strategies.

In inpatient or residential settings

Mental health professionals working in inpatient or residential settings, where individuals may be receiving intensive mental health care, may use the SIT Scale to assess and address self-injury trauma within the context of a structured treatment environment.

Research and clinical studies

Researchers and clinicians involved in studies related to self-injury may use the SIT Scale to measure the impact of self-harming behaviors within specific populations. This can contribute to a deeper understanding of self-injury's psychological and emotional consequences.

It's important to note that the decision to apply the SIT Scale should be based on clinical judgment and the client's individual needs. The scale is a tool for gathering information and guiding treatment, not a standalone diagnostic tool. Additionally, ethical considerations, including obtaining informed consent and ensuring the individual's well-being, should be prioritized when using assessment tools like the SIT Scale in clinical practice.

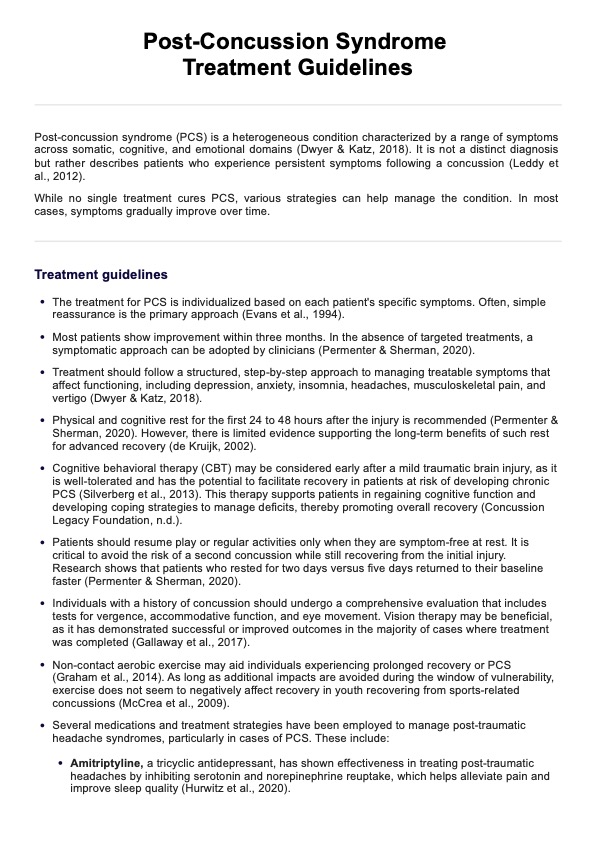

Next steps: trauma treatment

The next steps in self-injury trauma treatment depend on the individual's specific needs, the severity of their self-injurious behaviors, and the underlying causes of their trauma. It's crucial to emphasize that professional guidance is essential in developing a tailored treatment plan. Here are general steps that might be considered:

- Comprehensive assessment: Conduct a thorough evaluation to understand the individual's history, mental health, trauma experiences, and factors contributing to self-injury. This may involve collaboration between mental health professionals, including psychologists, psychiatrists, or therapists.

- Safety planning: Establish a safety plan to address immediate concerns related to self-injury. Identify coping strategies, support networks, and crisis intervention methods to ensure the individual's safety during challenging moments.

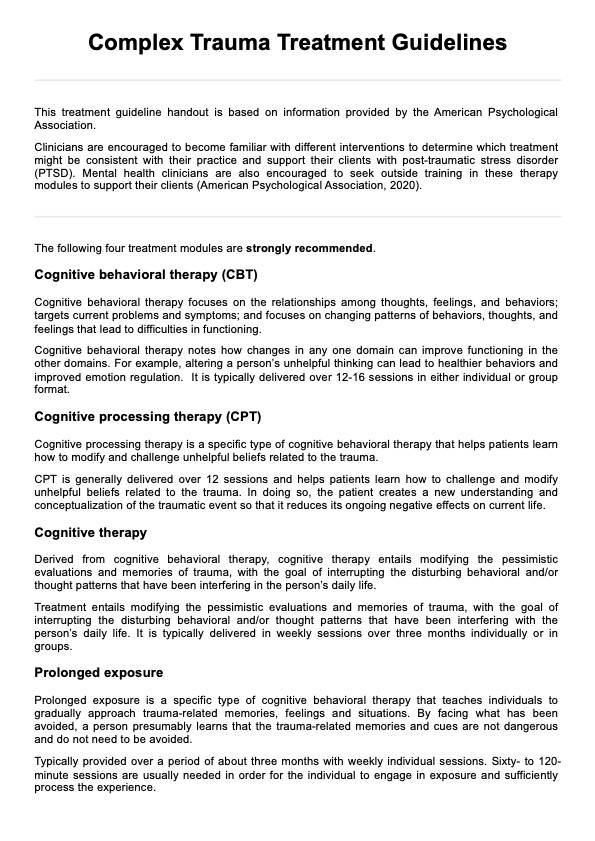

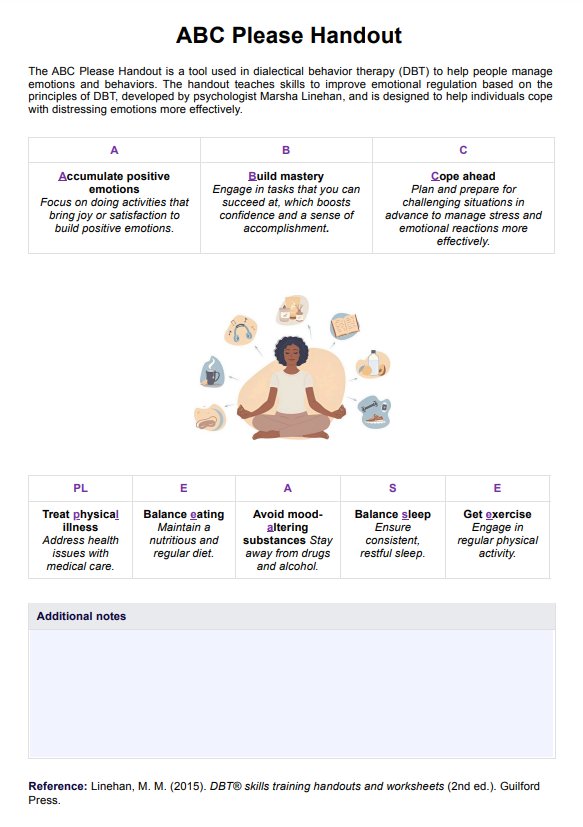

- Psychotherapy: Engage in psychotherapy, particularly evidence-based approaches such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), or trauma-focused therapy. These therapies aim to address underlying emotional pain and trauma and teach healthier coping mechanisms.

- Trauma-focused interventions: If trauma is a significant factor, trauma-focused interventions, such as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) or trauma-focused CBT, may be beneficial in processing and resolving traumatic experiences.

- Medication management: Medication management may be considered depending on the individual's mental health and symptoms. Antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or anti-anxiety medications may be prescribed to address underlying psychiatric conditions.

- Group therapy and support: Participation in group therapy, support groups, or peer support networks can provide a sense of community and understanding. Sharing experiences with others who have struggled with self-injury can reduce feelings of isolation.

- Family involvement: Involving family members in the treatment process can be essential, fostering understanding, support, and open communication. Family therapy may help address relational dynamics and improve the overall support system.

- Skill-building and coping strategies: Work on developing healthy coping strategies to replace self-injurious behaviors. This may include learning emotion regulation skills, mindfulness techniques, and stress management strategies.

- Addressing co-occurring issues: If there are co-occurring issues such as substance abuse, eating disorders, or other mental health conditions, these should be addressed simultaneously within the treatment plan.

- Continued monitoring and adjustment: Regularly monitor the individual's progress and adjust the treatment plan as needed. Flexibility in the approach allows for modifications based on the individual's response to interventions and changing circumstances.

- Collaboration with healthcare providers: Ensure collaboration between mental health professionals, primary care physicians, and other healthcare providers involved in the individual's care. This promotes a holistic approach to treatment.

Remember that the treatment process is highly individualized, and what works for one person may differ. The involvement of a skilled and compassionate mental health professional is crucial in guiding and supporting the individual through their journey to recovery from self-injury trauma.

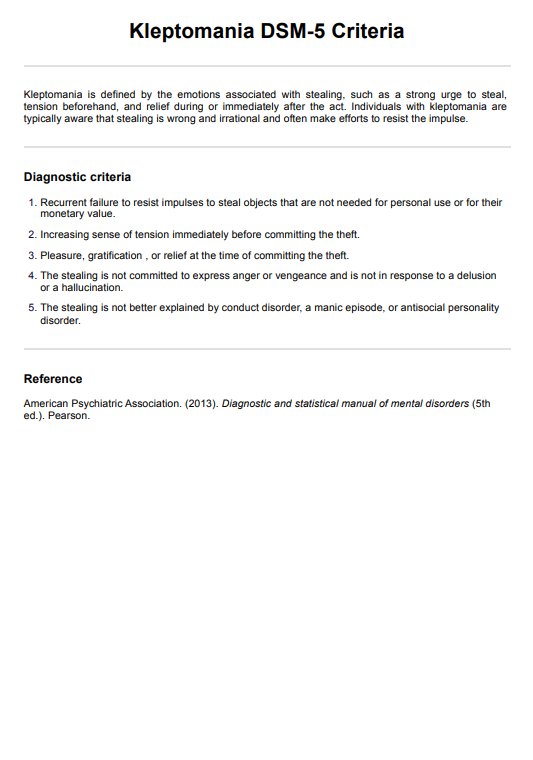

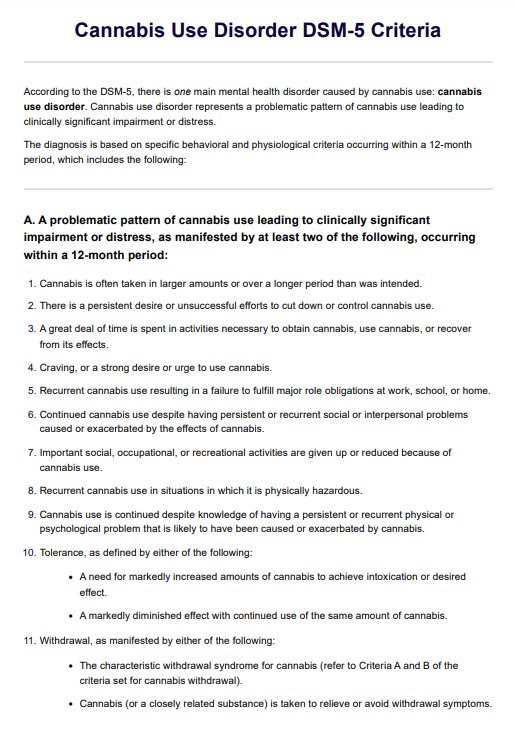

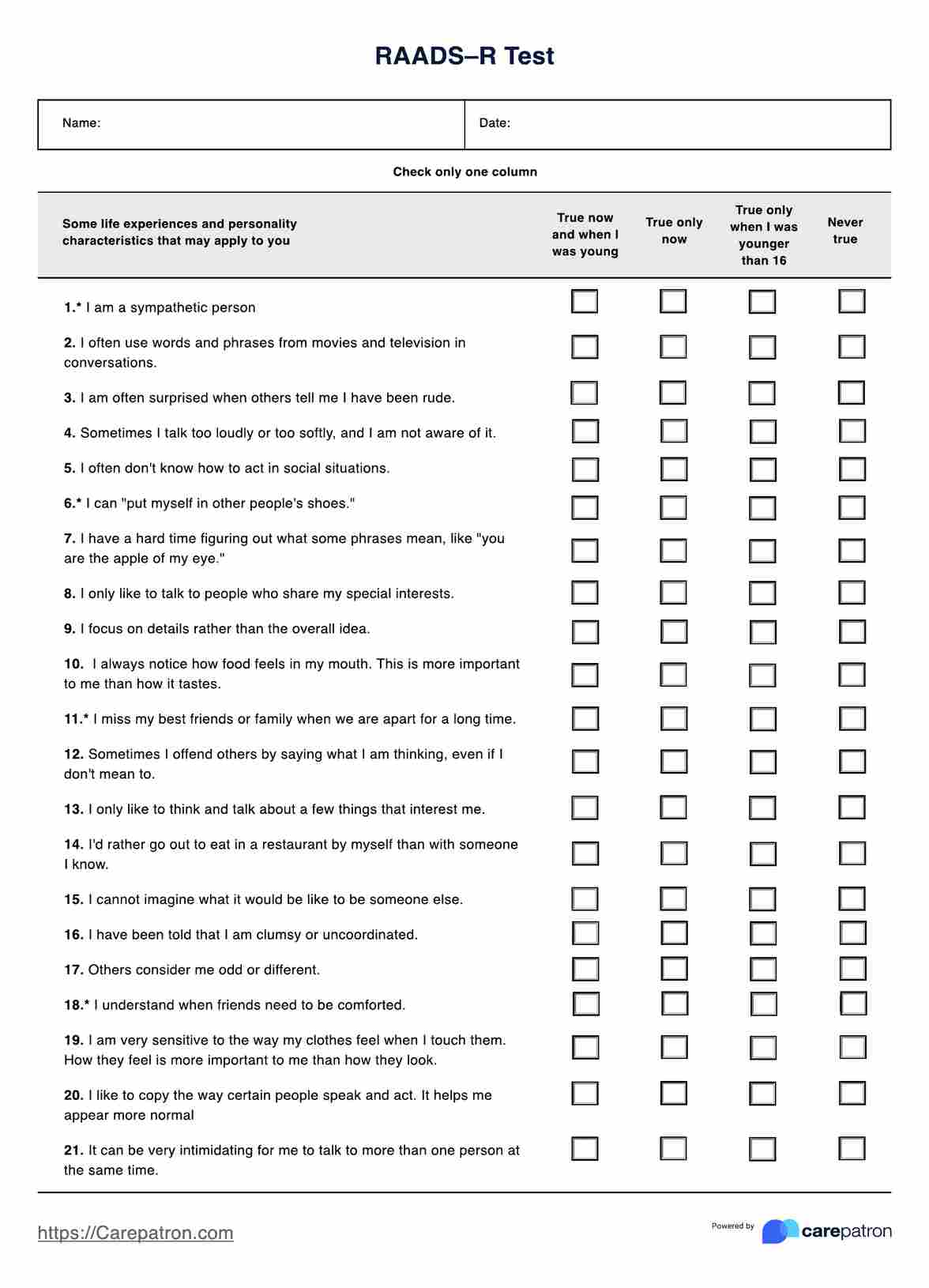

Research and evidence

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) involves intentionally causing harm to one's own body without suicidal intent (Nock & Favazza, 2009). Traditionally, NSSI has been considered a symptom of borderline personality disorder since its inclusion in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980). However, recent research challenges this perspective, revealing that NSSI is associated with various internalizing, externalizing, and personality disorders and can occur without specific psychiatric diagnoses (Glenn & Klonsky, 2013).

The understanding that NSSI is exclusively tied to borderline personality disorder has been shifted due to recent evidence suggesting that NSSI is a transdiagnostic phenomenon. Studies indicate that the risk of NSSI does not significantly differ across various psychiatric disorders (Bentley et al., 2015), emphasizing its distinct nature. This recognition is reflected in the DSM-5, which includes NSSI in the Conditions for Further Study section.

NSSI is more prevalent among women, with clinical samples exhibiting more significant gender differences (Hooley & Franklin, 2017). Women are also more likely to use self-cutting as a method of NSSI. Ethnic and racial differences in prevalence exist, with some studies suggesting higher rates among White and multiracial individuals. Sexual and gender minorities also exhibit higher rates of NSSI (Hooley & Franklin, 2017).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Bentley, K. H., Cassiello-Robbins, C. F., Vittorio, L., Sauer-Zavala, S., & Barlow, D. H. (2015). The association between nonsuicidal self-injury and the emotional disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.006

Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2013). Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder: An Empirical Investigation in Adolescent Psychiatric Patients. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(4), 496–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.794699

Hooley, J. M., & Franklin, J. C. (2017). Why Do People Hurt Themselves? A New Conceptual Model of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(3), 428–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617745641

Iwata, B. A., Pace, G. M., Kissel, R. C., Nau, P. A., & Farber, J. M. (1990). THE SELF-INJURY TRAUMA (SIT) SCALE: A METHOD FOR QUANTIFYING SURFACE TISSUE DAMAGE CAUSED BY SELF-INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1990.23-99

Nock, M. K., & Favazza, A. R. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. Understanding Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Origins, Assessment, and Treatment., 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/11875-001

Commonly asked questions

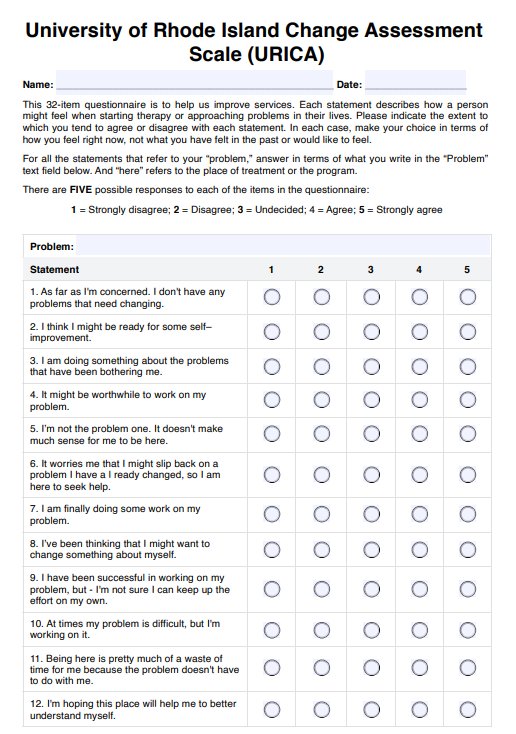

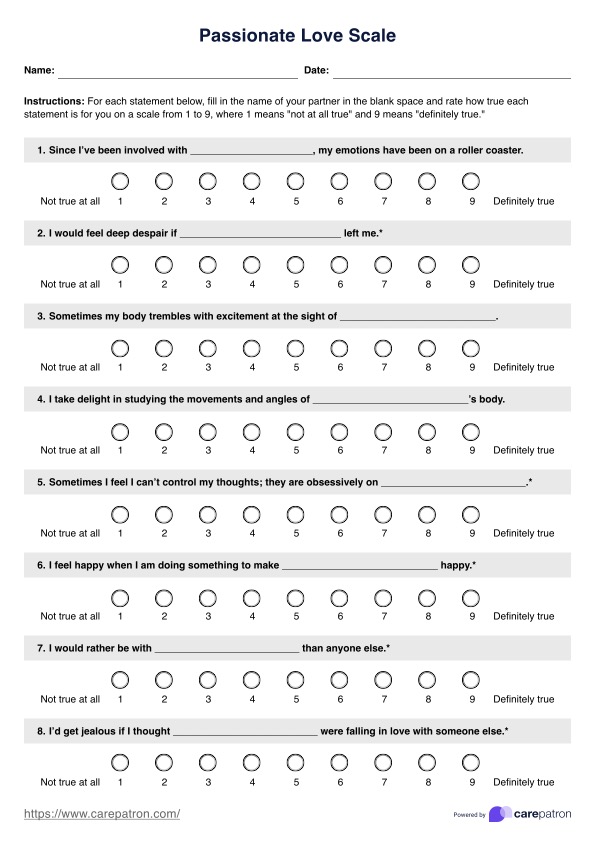

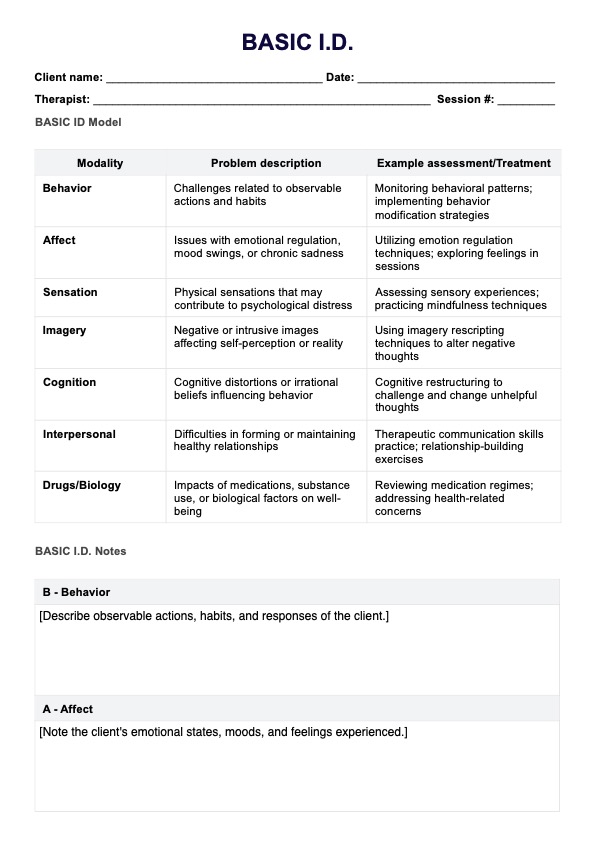

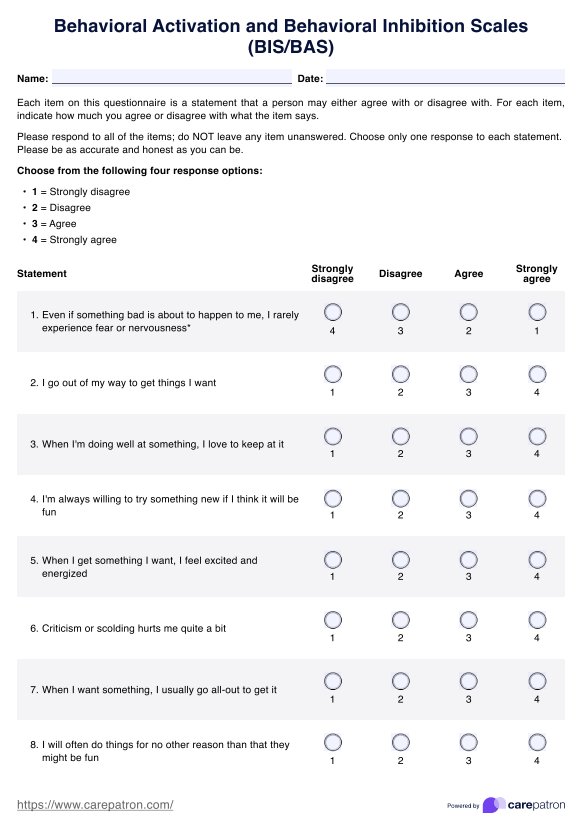

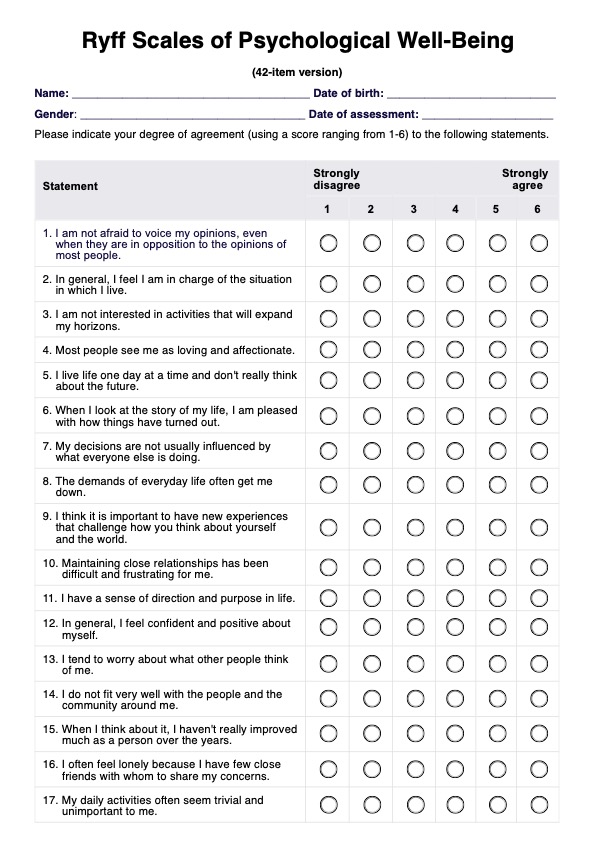

The SIT Scale is designed to measure the impact of self-injurious behavior on individuals in terms of trauma. It assesses the psychological and emotional consequences of engaging in self-harm, providing insights into the severity of trauma associated with self-injury. Mental health professionals use the SIT Scale to inform treatment planning, intervention strategies, and progress monitoring in individuals who engage in self-harming behaviors.

The scoring of the SIT Scale is typically based on a set of guidelines provided by the test developers. Specific criteria assign scores to individual responses, which are then aggregated to generate a total score. Higher scores generally indicate a more significant impact of self-injury-related trauma.

No, the SIT Scale is not a diagnostic tool on its own. Instead, it is an assessment instrument used by mental health professionals to gather information about the psychological and emotional impact of self-injury. While the scale provides valuable insights into the individual's experiences, a diagnosis typically involves a comprehensive clinical evaluation considering multiple factors.

-template.jpg)